Am – I Remember the Devotion of Your Youth 2: 1-13

I Remember the Devotion of Your Youth

2: 1-13

I remember the devotion of your youth DIG: God pictures Isra’el as a bride. Why is it such an apt illustration? What does it reveal about YHVH’s message about marriage? How did the marriage start out? To what barren wilderness does the LORD refer? What went wrong? What did the priests and the false shepherds do that was so contrary to ADONAI’s intent? Where was Ha’Shem all that time? What effect did this have? What charges does God bring? Ba’al is Hebrew for master or lord. Who is Ba’al (see Judges 2:11-13)?

REFLECT: What emotions do you think ADONAI is trying to convey through these vivid pictures? This is spiritual adultery. How do you feel when cheated upon? Do you think YHVH is hurt any less by those He loves? When was the last time you found yourself in a hole of your own making? Are you still there? Or did you get out? Did you get out by your own best thinking or by the grace of God? What’s the lesson?

626 BC during the reign of Josiah

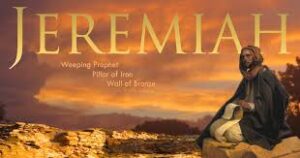

Here begins a series of brief oracles (divine communication or revelation), most of which seem to have come from Jeremiah’s early ministry. The first passage (2:1-13) contains two oracles that develop one thought. ADONAI contrasts Isra’el’s early devotion during the Exodus period with the apostasy after entering the Promised Land. The LORD calls upon the heavens to be shocked at this betrayal. The second oracle (2:14-19) shows the sad consequences of forsaking God. The third (2:20-28) defines Isra’el’s sin as idolatry. In the concluding oracle (2:29-37) YHVH tells how He has warned Isra’el, whom the prophet pictures as an adulterous wife. It is particularly in the oracles recorded in Chapters 2 and 3 of Jeremiah that we become aware of the links with Hosea both as to vocabulary and also ideas. Chapter 2 contains some of the finest poetry in the entire prophecy.28

A Divine Memory: Jeremiah’s first message confronted Jerusalem with her spiritual adultery. To emphasize this, the prophet contrasted Judah’s former devotion with her present waywardness. The word of the LORD came to me (2:1). No indication is given as to how the word of ADONAI came to Yirmeyahu, but like other prophets he had a strong sense of conveying the mind of God to His people. The Spirit spoke through the prophet. It was the way divine revelation came to mankind: For prophecy never had its origin in the human will, but prophets, though human, spoke from God as they were carried along by the Ruach HaKodesh (Second Peter 1:21).

Go and shout in the ears of Yerushalayim that this is what ADONAI says: I remember your devotion (Hebrew: chesed) when you were young; how, as a bride, you loved Me (2:2a CJB). The word remember here is not a word that is used in the TaNaKh to simply recall something, but to remember to one’s account so it may put one in a positive light afterwards (Nehemiah 5:19, 13:22-31; Psalms 106:45). As a result, here, ADONAI remembers something, and what He remembers is being placed in Isra’el’s account positively. And to some degree this positive element may offset some of the negative aspect of their relationship. God remembers three things: Isra’el’s devotion, their short honeymoon and their exodus through the wilderness.

Jeremiah follows Hosea’s reasoning and uses some of the same wording (Hosea 2:15, 9:10, 11:1-2). The mind of YHVH went back in memory to the days of Isra’el’s youth when she first entered into a covenant with Him. He intended that Isra’el should remember (Hebrew: zakar), and her great calendar of festivals were designed to keep that memory alive. The LORD recalled the unfailing devotion of Isra’el in her honeymoon period in the desert following her acceptance of His covenant. One is reminded of Hosea 1-3 where the husband-wife relationship between Hosea and Gomer is a picture of the relationship between Ha’Shem and Isra’el.

At the time of the exodus Isra’el followed ADONAI through the wilderness, through a land not sown (2:2b CJB). Isra’el wasn’t perfect (see the commentary on Exodus, to see link click Cn – When They Came to Marah the Water was Bitter), but God was gracious to her and for the most part she had remained faithful as a nation. The measure of Isra’el’s loyalty and devotion in those early days was that she ventured into the wilderness, an open area that had not been sown. This was in contrast to what she had known in Egypt with its tilled land and abundant crops. But strong confidence in YHVH led Isra’el to follow Him into such unfamiliar territory, so deeply did she trust Him.29 After beginning with a marital metaphor, Jeremiah moves briefly to an agricultural metaphor.

Isra’el had been set apart as holy to the LORD (Exodus 19:6, 22:31 and 28:36), the first fruits of His harvest (2:3a). Rashi explains that the phrase first fruits refers to the first portion taken from the new crop, such as the wave-offering (see my commentary on Exodus Gj – Take the Other Ram, and Aaron and His Sons will Lay Their Hands on Its Head), which must be brought to the Temple as sacred and not eaten by the farmer. As the first fruits of the field are sacred, so is Isra’el, the first-fruits set apart to God. The mention of first fruits implies that He expects a later harvest of the goyim.

All who devoured her were held guilty, and disaster overtook them (see my commentary on Exodus Cv – The Amalekites Came and Attacked the Israelites at Rephidim). Although it was Jeremiah’s belief that those nations were carrying out God’s will, he knew that they were not motivated by any high or noble motive. For them it was simply a matter of aggression and lust for conquest, for which they would be punished. And disaster overtook them declares the LORD (2:3b). There is a principle written into Scripture that has held true down through the centuries. It was first told to Abram, but it still holds true today. ADONAI said: I will bless those who bless you, and whoever curses you I will curse (Genesis 12:3a). The contrast between this beautiful state and the sad unfaithfulness of the years that followed are reported next.

On Changing Gods: Hear the word of ADONAI, you descendants of Jacob, all you clans of Isra’el. This is what YHVH says: What fault did your ancestors find in Me, that they strayed so far from Me? God committed no wrong in the relationship. So the tone of the initial question is like the hurt of a wounded lover. They followed worthless idols and became worthless themselves. Isra’el had gone after the gods of Canaan and in the process became as useless to God as a rotten loincloth (see Dx – A Linen Loincloth). The apple of His eye had become like the gods she served (Psalm 115:8). The Hebrew word hebel is the same as used in Ecclesiastes and there it is regularly translated meaningless, pointless or vanity. It conveys vapor or unreality, an appearance that has no real substance.30 Not only was the honeymoon over . . . the whole relationship had fundamentally changed. What had been a happy marriage and a joyous offering had been deeply perverted, seemingly beyond repair.

What makes idols worthless? The short answer is that they are not divine and cannot save. Idols are a substitute for the real thing: counterfeit gods. Today it seems that people are not without their little gods of religious activity. Instead of believing in nothing, they are tempted to believe a little in everything in their search for “solutions” in this life. They search for the god within, and thus, worship themselves. Worthless!

They did not ask, “Where is ADONAI, who brought us up out of Egypt and led us through the barren wilderness, through a land of deserts and ravines, a land of drought and utter darkness, a land where no one travels and no one lives? Isra’el forgot their gracious delivery out of Egypt. He said: I brought you into a fertile Land to eat its fruit and rich produce. Ha’Shem, unlike Isra’el was true to His word. How good the relationship used to be! But you came and defiled My Land with idol worship and made My inheritance detestable (2:4-7). How things had changed!

Then the LORD gives the indictment against Isra’el . . . The priests Levites did not ask, “Where is the LORD?” Those who deal with the Torah did not know Me (2:8a). Their whole relationship with Elohim was reduced to nothing (Hosea 4:4-10). False shepherds (23:1) rebelled against Me. Priests no longer provided serious leadership. Judges forgot the central commitment to justice. Rulers forgot that power is a trust from YHVH. Jeremiah discerned the collapse of public institutions.

The prophets prophesied by Ba’al and followed worthless idols (2:8b), and broke both the first and second commandments (Exodus 20:3-4). Isaiah mocked the making of these worthless idols (see my commentary on Isaiah Hy – Worship the LORD, Not Idols). Despite various revivals under Asa, Hezekiah and Josiah, the people continually reverted to the deities and rituals of Canaan. Here ADONAI raises the deeply personal matter in a highly intense and emotional way. An intimate relationship had been broken down, and this had produced strong feelings of anger and hurt on God’s part. This is a divine lament, and to hear it in these opening verses is important to the interpretation of the scroll as a whole. So Yirmeyahu begins with a portrayal of YHVH in deep anguish and pain.31

Having clearly shown the faithlessness of the people, Jeremiah used an image of a court case to focus on the seriousness of Isra’el’s sin. Therefore, I bring charges (Hebrew: rib, a legal term for filing a lawsuit as in Micah 6:1-2) against you again, declares ADONAI. And I will bring charges against your children’s children (2:9). If the audience thought it could get off by agreeing with the failures of the Eli priesthood, to scribes over the years who wrote about YHVH but did not know him, to irreligious kinds from Jeroboam son of Nebat (First Kings 11:26) to the more recent Manasseh, and to hordes of Ba’al and Asherah prophets who earned their place at Jezebel’s table by prophesying homegrown nonsense . . . they were wrong. Ha’Shem’s complaint was with those listening to the oracle, and more sadly still, to their grandchildren. The LORD said very plainly, “My complaint is with you!”32

The prophet asked the Israelites to go on a “field trip” to observe the faithfulness of the Gentiles. Whether they went to the coasts of Cyprus in the west or to Kedar (north Arabian desert tribes) in the east, the results would always be the same. No pagan society had ever changed its gods (Yet they are not gods at all)? The idolatrous nations surrounding Isra’el were more faithful to their false gods than Isra’el had been to the true Master of the universe.33 But, the LORD lamented, My people have exchanged their glorious God for worthless idols. They were not able to determine what was real and unreal, what was true and false, and what was life giving and death dealing (Romans 1:20-25). Heaven and earth function as witnesses (Isaiah 1:2) who guarantee oaths and who observe patterns of faithfulness and fickleness. Because heaven and earth know YHVH to be the One True God (Psalm 96:11), Isra’el’s despicable response to ADONAI is exposed for what it is. In this cosmic court there is no doubt about who is the guilty party. Be appalled at this, you heavens (Deuteronomy 32:1), and shudder with great horror, declares the LORD (2:10-12).

On living water: The poem introduces the metaphor of living water and empty cisterns. My people have committed two sins. Note that in spite of their sins, God calls Isra’el my people (2:11, 13, 31-32) and children (3:14, 22) and is still identified as your God (2:17,19) and your Master (3:14). Once again, the exiled Israelites are in view here. First, ADONAI says: They have forsaken Me, the spring of living water (2:13a).

And, second, God laments: They have dug their own cisterns, broken cisterns that cannot hold water (2:13b). The dryness of the summer months in Palestine, and the absence of large rivers, together with the scarcity of springs in many places, makes it necessary to collect into cisterns the rains which fall, and the waters which fill the small streams in the rainy season. This has been the custom in that land from very early times. These cisterns are either dug in the earth or cut out of the soft limestone rock, and there are several kinds. Sometimes a shaft is sunk like a well, and the bottom widened into the shape of a jug. Digs of this sort combine the characteristics of cisterns and wells, since they not only receive the rain that is conducted into them, but the water that percolates through the limestone. Another kind consists of chambers excavated out of the rock, with a hole in the roof. Again, an excavation is made perpendicularly, and the roof arched with masonry. Some are lined with wood or cement, while others are left in their natural state.

Sometimes they are entirely open at the top, and are then entered by steps, or, in the case of large ones (and some are very large), by flights of stairs. When they are roofed, a circular opening with a lip at the top, and a pulley, with a rope and bucket is provided. This is referred to in Ecclesiastes 12:6, and the pulley is broken at the cistern.34 With proper care the water may be kept sweet for a time; however, even with the best of care, even those hewn from solid rock are bound to crack. So the water collected from the clay roofs or from marly soil has the color of weak soapsuds, the taste of the earth or the stable, is full of worms, in filthy condition, and not to be compared with the pure water from living fountains. At any time the cisterns are liable to break and leak. So these cisterns are now broken and they cannot hold water. This is one of the images of apostasy that we will see in Chapter 2.

This verse is one of the most beautiful and meaningful passages in the entire prophecy; it is applicable today. People still turn from the life-giving source and, with incredible labor, make substitutes that inevitably disappoint them. The verse continues an earlier thought, those who pursue worthlessness become worthless themselves (2:5). A thirsty person who turns to an empty cistern will become even more thirsty.35 There will surely be a plucking up and a tearing down of one so faithless, who in this poem is none other than Yerushalayim.

Yeshua returned to the living water metaphor with a Samaritan woman at Jacob’s well when He said: Everyone who drinks this water (from Jacob’s well) will be thirsty again, but whoever drinks the [living] water I give them will never thirst. Indeed, the water I give them will become in them a spring of water welling up to eternal life (John 4:13-14). And later at the last and greatest day of Sukkot, He declared: Let anyone who is thirsty come to Me and drink. Whoever believes in Me, as Scripture has said, rivers of living water will flow from within them. By this He meant the Spirit, whom those who believed in Him were later to receive. Up to that time the Holy Spirit had not been given, since Jesus had not yet been glorified (John 7:37b-39).

Such a critique of the life of God’s people invites every generation of His people to reexamine its own commitments. As is common with the prophets, the criticisms of Yirmeyahu here do more than explain what was wrong in his own day, they also intend to ask subsequent generations to examine our lives and witness.