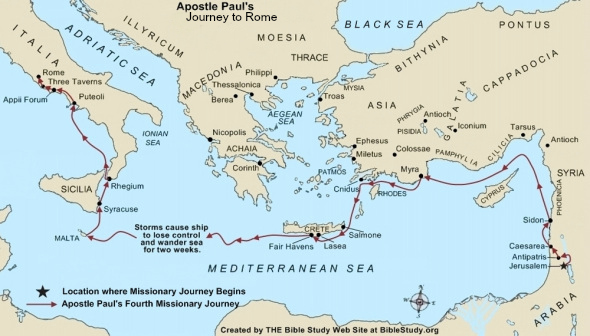

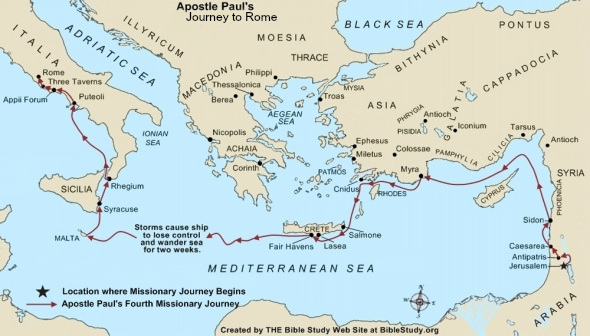

Dc – The Shipwreck at Malta 27: 27-44

The Shipwreck at Malta

27: 27-44

Late 59 AD

The shipwreck at Malta DIG: Compare verse 31 with verse 11. What do you think the centurion feels about Paul now? About the God Paul serves? How do Paul’s words and example serve to encourage the others? How would your estimation of Paul have changed during the two-week storm? What do you imagine the scene in verses 39-44 was like? What was said? How did people look? Feel? How do Paul’s attitudes and actions compare with those of the sailors? To what would you attribute Paul’

REFLECT: What are some of the blessings you’ve experienced because of the wisdom and faithfulness of others? How would it affect your own daily battle with sin and selfishness if you knew that your obedience was as important to those around your as it is to you yourself? When have you reacted in crisis as Paul did – urgent forewarnings, maintaining hope, counseling, common sense, giving thanks, remaining calm, persevering to the end? What is the greatest pressure situation you’re facing now? How can Paul’s example and the principles you’ve learned from this story help you in your situation? What is your part and what is God’s part in the resolution of your storm? When have you been tempted to bail out of a stormy situation, to sneak away in a lifeboat? What happened? What did you learn? What weaknesses of Jonah can you most relate to? What strengths of Paul do you most wish to obtain?

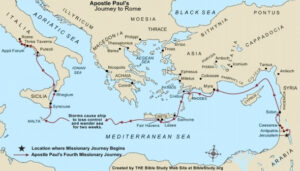

The tempest had driven the drifting ship for two weeks. Now when the fourteenth night had come, as we (to see link click Bx – Paul’s Vision of the Man of Macedonia: A closer look at the “us” or “we” passages and sea passages)were drifting about 476 miles off course across the Adriatic Sea. The Adriatic Sea mentioned here is not to be confused with the modern Adriatic Sea, located between Italy and Croatia. In Paul’s day, that body of water was known as the Gulf of Adria, referring to the central Mediterranean.624 It is bordered on the north by Italy, on the west by Sicily, on the south by Cyrene, and on the east by the island of Crete. Approaching the bay the breakers were especially violent and noisy.

About midnight the sailors began to hear breakers and sense that they were nearing some land. The crew was afraid of running onto the rocks in the dark, so they took soundings and found the water was twenty fathoms deep. Standard practice as the ship approached land was to check the depth of the water at half-hour intervals. One fathom is six feet, so at that point they were 120 feet above the floor of the ocean. A bit farther along, they took another sounding and found it was fifteen fathoms deep, or 90 feet. Yes, they were getting closer to the land. But fearing that they might run aground on the rocks, they threw out four anchors from the stern to stop the ship (27:27-29). Paul, Luke and Aristarchus (27:2) had been praying (Greek: euchomai) to ADONAI for day to come, and the other men on board were probably praying to their various pagan gods as well.

Now some of the sailors were trying to escape from the ship and save themselves and get to land at the expense of the others on board. Evidently they didn’t trust their gods to deliver them and decided to take matters into their own hands. They had lowered the dinghy into the sea, pretending they were going to put out anchors from the bow. This would have seemed to be a perfectly natural operation. Anchors from the bow, or the back of the ship, would have given the ship even greater stability, and it would have been necessary to set them out some distance from the ship, which could only have been accomplished by using the dinghy. Paul, however, realized their true motive and said to the centurion, “Unless these men remain on the ship, you cannot be saved” (27:30-31).

But hadn’t God already promised that would be no loss of life (27:22)? Think of it this way; the prophecy includes God’s foresight concerning decisions that are nevertheless made by free will. If the sailors had left the boat, would the centurion and his soldiers’ lives have been saved? This is a hypothetical question that need not be answered, since that is not what happened, and we have no framework for dealing with such questions. Once again we are reminded of Rabbi Akiva’s summary of the paradox, “All is known, yet free will is given” (Avot 3:15).

Moreover, in the Bible, even what appears to be an absolute prediction (X will happen) may be implicitly conditional (If you disobey, X will happen). Jonah’s apparently unconditional prediction of Nineveh’s destruction is a good example (see the commentary on Jonah Ax – The Ninevites Believed God). The prophet was wrong (and angry about it) because the people of Nineveh repented (which, rather than the city’s ruin, is what God actually wanted). Why did the sailors need to remain on board? It was a practical matter. Had they left, there would not have been enough skilled personnel left to beach the ship when the time came. Learning to respect Paul’s direction, the soldiers cut away the ropes of the dinghy and let it drift away empty (27:32).625

With the thwarted attempt of the sailors, a ship badly battered by the storm, and no assurance they could get safely to shore, Paul once again rose to encourage the shaky voyagers. As day was about to dawn, Paul continually urged them all to take some food, saying: Today is the fourteenth day that you have kept waiting and going without food, having taken nothing. Luke’s point in this hyperbole is that it had been a long time since they had had much to eat.626 Paul need them to strengthen themselves for the last hurtle, getting from the ship to the shore. Therefore, I urge you to take some food – literally, for this is for your salvation (Greek: soteria, meaning salvation). There may be a veiled symbolism in the use of this word, a reminder to the believing reader that the same God who delivered the storm-tossed voyagers from physical harm is the God who in Messiah brings ultimate salvation and true eternal life. The theme is not developed Luke’s narrative, however, and remains implicit at most. There is in fact no explicit reference to Paul’s witnessing in the entire voyage narrative from 27:1 to 28:16, though one cannot imagine Paul bypassing the opportunity. The emphasis at this point is the physical rescue. Since not one of you will lose a hair from his head (27:33-34). This was a proverbial expression for physical salvation seen in First Samuel 14:45; Second Samuel 14:11 and First Kings 1:52, also in the B’rit Chadashah in Matthew 10:30; Luke 12:7 and 21:18. God had provided their physical salvation by means of eating.627

And when he had said these things, like a good Jewish father beginning a family meal, he set the example, took bread, and said the b’rakhah that Jews normally make over bread: Barukh Attah, Adonai Eloheynu, Melekh-ha’olam, hamotzi lechem min ha’aretz (Praise be you, Adonai our God, King of the universe, who brings forth bread from the earth, see Matthew 14:19). Then, he broke it and began to eat. Then all were encouraged. And because their appetite had returned, they took some food themselves. In all we were 276 persons on the ship. When they had eaten enough – being revived both physically and emotionally – they began to lighten the ship, throwing the rest of the wheat into the sea (27:35-38). That way the ship would sit higher in the water and allow it to slide as far up the beach as possible before being beached.

Then when daylight came, they did not recognize the land because it was not on the normal sea route; but despite the stormy conditions, they noticed a bay with a beach, where they planned to run the ship aground on the sand, and avoid the rocks if they could. The rudder of the ancient ships consisted of four large paddles, one on each quarter. In a storm these would be lifted from the water and tied down. Now, to guide the ship for the beaching, they were untied and let back down into the water.628

They also cut off the anchors and left them in the sea. Then, hoisting the forward sail to the wind to pick up speed, they made for the beach. But, despite their best efforts, the ship struck a sandbar between the seas and ran the ship aground before it reached the beech. The bow stuck fast and remained immovable, and the stern began to break up by the pounding of the waves (27:39-41). When a swell reaches an island, its waves split to pass it, and they may meet head on at the far end of the island. At this place, the sand carried along by the currents from both directions are deposited as a sandbar, on which the waves break from two nearly opposite directions, sometimes even running straight into each other. Such a spot is very treacherous for ships.629 The ship was stuck in the sandbar perhaps fifty yards from the shore, giving even those unable to swim a good chance of survival. At that point there was nothing else to do but abandon ship.

Roman military discipline made soldiers personally responsible for their prisoners, and those who allowed their captives to escape could pay with their own lives. Acting without orders, the plan of the soldiers was to kill the prisoners so that none of them would escape by swimming away. But again, it was Paul who provided for the safety of his fellow prisoners. Julius, wanting to save Paul, risked his own life by keeping them from carrying out their plan. Whatever the centurion’s attitude to the other prisoners might have been, he was unwilling to put Paul’s life in danger, especially in view of his leadership during the voyage.630 So he ordered those able to swim to throw themselves overboard first and get to land – and the rest to get there on boards and pieces of the ship. And in this way all 276 were brought safely to land (27:42-44). Thus, Paul’s prophecies of 27:22-24 and 34 were fulfilled.

Let’s allow God to open our eyes to the importance of faithfulness and obedience through a study in contrasts, by seeing the umbrella of protection or destruction in one person’s hand can often cover many heads. The kind of cover these figurative umbrellas provide is not only determined by belief in God versus unbelief, but also by faithfulness verses unfaithfulness.

In Acts 27, God gave Paul an umbrella of protection because of his obedience in ministry. Whether or not the others on board his sinking ship realized it, many were gathering under his umbrella and found safety. But let’s take a look at another kind of umbrella in the storm, on display in the familiar account of the prophet Jonah. You’ll recall that God called him to go preach to the people of Nineveh (see the commentary on Jonah Aj – The Word of the LORD came to Jonah: Go to Nineveh), but Jonah ran the other way (see the commentary on Jonah Ak – Jonah Flees From the LORD), booked a passage to Tarshish and wound up in a whale of a mess (see the commentary on Jonah Ar – The LORD Prepared a Great Whale to Swallow Jonah). Consider the similarities between Paul and Jonah.

- Both were Hebrews, had Jewish backgrounds, and believed in the one true God.

- Both were preachers.

- Both were called to preach unpopular messages in pagan cities.

- Both boarded a ship.

- Both experienced a terrible, life-threatening storm.

- Both greatly impacted the rest of the crew.

- Both knew the key to the crew’s survival.

Paul and Jonah hand many similarities, didn’t they? But let’s consider a few contrasts between the two. They differed in the following ways.

- Paul was compelled to go to Rome; while Jonah was repelled by his calling to Nineveh.

- Paul faced many obstacles on his way to Rome, including imprisonment, injustices, inclement weather, and other difficulties; while Jonah’s only obstacle was himself.

- Paul had to sit and wait for the Lord; while Jonah stood and ran from Him.

- Paul felt responsibility for the crew, although the calamity was not his fault; while Jonah slept while the others worked to survive the calamity he had brought upon them.

Paul and Jonah are great characters to compare and contrast because we can relate to both of them! Sometimes we respond with obedience like Paul. Other times we run from God like Jonah.

Let’s ask a fair question based upon their examples: Does prompt obedience really make a difference? When all was said and done, didn’t Paul suffer through a terrible storm although he had been entirely obedient? Didn’t Jonah get another chance to obey, and an entire city was spared? So . . . what difference does prompt obedience or faithfulness make anyway?

God loves us whether or not we are obedient, but the quality of our lives as believers is dramatically affected by our response. There is a big difference between an obedient believer and a disobedient one, between obedient and disobedient times. Yeshua said: If you keep My commandments, you will abide in My love, just as I have kept My Father’s commandments and abide in His love. These things I have spoken to you so that My joy may be in you, and your joy may be full (John 15:10-11). Although Jonah was ultimately obedient and surprisingly successful, you will search in vain for a single hint of joy in his life. Although Paul seemed to suffer at every turn, he had more to say about joy than any other mouthpiece in the Word of God.

An attitude of obedience makes a difference both to the servant and to those close by. Servants of God can dramatically affect the lives of others positively or negatively. Under Jonah’s umbrella in the storm, many experience calamity; under Paul’s umbrella, however, many found safety.

Is the sky rumbling? Are clouds darkening? Is a storm rising in the horizon? Child of God, you will hold an umbrella in the storm. You will not be under the umbrella alone. Neither will I. Our spouses and children will be under the umbrella with us. Our friends, relatives, neighbors and coworkers will be there also. The flocks that God has entrusted to us will be there. Even the lost are often drawn to people of faith when the hurricane winds begin to blow. Child of God, all eyes are on us on the bow of the ship when the storms come and the waves crash. May the rest of the crew find an umbrella of blessing in our midst.631

That the assassins assumed the Sanhedrin’s leadership would take part in the murder plot says much about the apparent corruption of Isra’el’s highest court. Nor did the Sanhedrin disappoint them (23:20).

That the assassins assumed the Sanhedrin’s leadership would take part in the murder plot says much about the apparent corruption of Isra’el’s highest court. Nor did the Sanhedrin disappoint them (23:20).

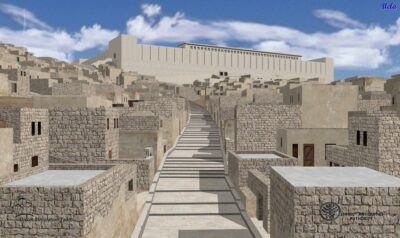

called the Chamber of the Nazirites, where they would cut their hair and solemnly burn it, along with a Peace Offering (see the commentary on

called the Chamber of the Nazirites, where they would cut their hair and solemnly burn it, along with a Peace Offering (see the commentary on