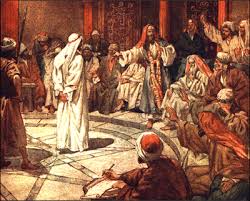

Stephen’s Testimony to the Sanhedrin

6:8 to 7:53

31-33 AD

The events of Acts 3-8 transpire with mounting concern on the part of the Jews, and especially the Jewish authorities in Yerushalayim. The rising tension resulted in vigilante action taken against Stephen, and then an authorized effort under Rabbi Sha’ul to disrupt and destroy that new Messianic movement, involving persecution and even death of the believers. The persecution led various belivers such as Philip to go to Samaria and bear witness of Yeshua.

Stephen’s testimony to the Sanhedrin DIG: From 6:13-14, how would you write up the formal charges against Stephen? What does Stephen’s defense (in effect a history lesson) reveal about his respect for the Torah? Why did Stephen spend the bulk of his defense speaking about Moshe? What parallels did he make between Moshe and Yeshua? How did that relate to the charges against him in 6:13-14? How does the quote in verse 37 begin to turn the tables on his accusers regarding who was really rejecting Moses? From verses 44-50, what is Stephen’s point about the Temple and God’s presence? How is he turning the tables against his accusers once again? Look at Deuteronomy 10:16 and 30:4. What does Stephen mean by the phrase uncircumcised hearts and ears? In this context, what is Stephen really saying about the Great Sanhedrin’s regard for Moshe and the Torah? Of what does he accuse them in verses 51-53? Therefore, considering the circumstances, what type of a person was Stephen?

REFLECT: Since the Great Sanhedrin knew their history every bit as well as Stephen, how do you account for the radically different response to Jesus? What is needed in your life besides knowledge to fully understand Messiah? In what ways do people hold on to religious rituals and heroes today, while missing the whole point of what those ceremonies and people represent? How does this tendency affect you? In what ways could the charges that Stephen makes against the Jewish leadership be made against you? How might you be feeling “stiff-necked” this week? How will you begin to bow to YHVH in that area now? Would you say that the TaNaKh is more like a stranger or a close friend to you? When Yeshua was brought to trial, He was basically quiet before the Great Sanhedrin; yet Stephen spoke very boldly here. How do you decide when to speak boldly and when to be quiet before your opposition?

This passage marks a transition in the book of Acts. Up to this point, Peter has been the dominating figure, fulfilling his calling by taking the gospel to the Jews first (Romans 1:16). But another major figure looms on the horizon: Rabbi Sha’ul, who is also called Paul (to see link click Bm – Paul’s First Missionary Journey), who is introduced at the end of Chapter 7. Bridging the gap between those two giants is Stephen. Peter ministered primarily to the Jewish people, and Paul primarily to the Gentiles. Peter ministered in Yerushalayim, Paul throughout the Roman Empire. But Stephen’s ministry was the catalyst that catapulted the Messianic community out of Judea, Samaria, to the ends of the earth (1:8).137

As Chapter 7 opens, Stephen’s trial begins. While the main thrust of Stephen’s speech was to answer the charges of blasphemy, three other ideas are interwoven throughout. First, he knew he must capture and hold his audience’s attention. He did that by reciting Isra’el’s history as the groundwork for his defense. Since the Sanhedrin was fiercely proud of their ancestry that was a topic they never got tired of hearing about.

Secondly, Stephen’s speech was to indict his hearers for rejecting the Messiah. Throughout his speech, that indictment slowly builds until it reaches a devastating climax (see An – Peter Speaks to the Shavu’ot Crowd: Speeches in Acts). He shows them that by rejecting the Messiah, they were imitating their apostate descendants, who rejected Joseph, Moshe, and even God Himself. Stephen was not the blasphemer, they were!

Thirdly, Stephen sought to present to them Yeshua as the Messiah, using Joseph and Moshe as types of Christ. This passage presents Stephen’s fourfold defense against the false charges of blasphemy brought against him. It is best not to get lost in the details of the references in the TaNaKh that Stephen cites, but instead, to concentrate on the dramatic themes and flow of his masterful message. Stephen’s purpose was not to recite history, but to establish that he was not guilty of blaspheming ADONAI, Moshe, the Torah, or the Temple. His accusers were, however, guilty of blasphemy because they had rejected the Messiah.138

Whatever the Jewish leaders thought, they must have been surprised at what they got next. Stephen stood accused. His life literally hung in the balance. But instead of placating his accusers or defending himself, Stephen preached one of the most classic sermons in history.139

ADONAI

Now Stephen addressed the most serious allegation first, accusing him of blasphemy against ADONAI. Being filled with the Spirit of God, Stephen was full of grace and power, was continually doing great signs and wonders among the people. The more Stephen poured out his life for Messiah, the more Messiah poured His life into Stephen. It is important to understand that his authority to perform great signs and wonders only came after he was appointed one of the seven deacons (see Av – Deacons Anointed for Service); in other words, it came only with the authority given to him by the apostles by the laying on of hands. This process will continue throughout the book of Acts. The ability to perform signs and wonders was not common among all the believers, but were only performed either by the apostles or those to whom they delegated, as was the case of Stephen. The Messianic community was not a miracle-working community. Rather, it was a Messianic community with miracle-working apostles.

But some men from what was called the Synagogue of the Freedmen – both Cyrenians and Alexandrians, as well as some from Cilicia and the province of Asia – were stirred to action and began arguing with Stephen that Yeshua was the Messiah (6:8-9). These men were probably Diaspora Jews who had been captured and enslaved by the Romans. General Pompey, who captured Jerusalem in 63 BC took a number of Jews prisoner and released them in Rome. Some, however may have been Gentile converts to Judaism. The phenomenon of proselyte zeal is familiar in all religious communities. But they could not withstand the wisdom and the Ruach by whom he was speaking (6:10). When Stephen’s opponents could not get the best of him in a fair debate, they changed tactics.

Then, with evil intent, they secretly instigated men into saying: We have heard him speaking blasphemous words against Moses and against God. This was the same tactic used at Messiah’s trial (Mattityahu 26:59-61; Mark 14:55-59). Even the trumped-up charges of blasphemy and speaking against the Temple were the same as those against the Lord. The fact that they also charged Stephen of blaspheming Moshe suggests he was denying the ability of the Torah to save. They charged him of blaspheming against God by speaking against the Temple by saying you could worship God anywhere. That accusation no doubt reflected Stephen’s presentation of Messiah as the embodiment of ADONAI. But that charge of blasphemy violated the laws of the Sanhedrin (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Lh – The Laws of the Great Sanhedrin Regarding Trials), because the Oral Law said that unless someone specifically pronounced the personal name of God – YHVH – they could not be accused of blasphemy. Since those same lies had worked so well against Yeshua, they were quick to use them against Stephen.

They also incited the people, members of the Sanhedrin, the elders, and the Torah scholars; and they rushed at Stephen as a mob, seized him, and forcefully led him away to the Sanhedrin. They set up two or three false witnesses who said: This man never stops speaking words against this Holy Place (which would appeal to the Sadducees) and the Torah (which would appeal to the Pharisees). For we have heard him saying that this Yeshua ha-Natzrati will destroy this place (once again angering the Sadducees) and change the customs that Moses handed down to us (once again angering the Pharisees), so they both had a reason to be angry against Stephen (6:11-14). By changing the customs, they meant disregarding the Oral Law (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Ei – The Oral Law). Because the rabbis taught that Moshe brought down the Oral Law from Mt Sinai at the same time, he brought down the Ten Commandments, an attack on the Oral Law was, in effect, tantamount to an attack on the Torah as a whole. Stephen had the utmost respect for Moshe and the Torah. Their choice of words, however, made him out to be a revolutionary, seeking to overthrow the established divine order. They turned his positive proclamation into a negative attack.

What happened next presented a striking contrast. Stephen stood before the Sanhedrin accused of being an evil blasphemer of ADONAI, Moshe, the Torah and the Temple. However, watching him intently, everyone who was sitting in the Sanhedrin saw that his face was like the face of an angel (6:15). Far from being evil, Stephen radiated the holiness and Sh’khinah glory of God, something no one else in history had experienced except for Moshe (Exodus 34:27-35). By putting His Sh’khinah on Stephen’s face, ADONAI showed His approval of the B’rit Chadashah and its messenger.140

The Pharisees instigated this third persecution of believers in Acts. It was no longer merely the Sadducees who were in opposition to the Messianic Community as had been during the first five chapters because the issue now being raised is no longer merely about the resurrection. The issue now is a new order, a new Way in opposition to Pharisaic Judaism.141

Having been charged, Stephen had the right to defend himself, therefore, a the cohen gadol (probably Caiaphas, who was in office until 36 AD) said: Are these things so (7:1)? In effect, he was asking, “How do you plead to the charges against you, guilty or not guilty?” But Stephen’s defense was hardly a defense in the sense of an explanation trying to win an acquittal. Rather, it was a proclamation of the Good News and an indictment of the Jewish leaders for their failure to recognize Yeshua as the Messiah, or to appreciate the salvation offered by Him.142

As Stephen begins his defense, critics of the inerrancy of the Scriptures, or opponents of messianic Judaism, like to point to several quotes from Acts 7 as proof texts. They try to show a sharp contradiction of what it says in the TaNaKh and Acts 7. They quote from Acts 7, and then they say, “Where in the TaNaKh does it say this?” There are two reasons for these seeming discrepancies: First, is the use of different texts. The TaNaKh that we now have is called the Masoretic Text. It is the oldest complete copy that we have of the TaNaKh compiled about 1,250 AD. Being a Hellenist, when Stephen quotes the TaNaKh he uses the Septuagint, or the Greek translation of the TaNaKh, compiled about 250 BC. The Hebrew text, which is the basis of the Septuagint is at least as old as that. However, the Masoretic Text only dates to 1,250 AD. So the question becomes, “Which text is more accurate? The Hebrew text behind the Septuagint, or the Masoretic Text?” If we go by what is closest to the original time of writing, the Septuagint is using a Hebrew text that is far older than the Masoretic Text. So one reason the verses in the Acts 7 don’t match the quotes in the TaNaKh is that Stephen used the Septuagint.

Second, is the use of a principal called telescoping, or combining two events into one picture. Critics say that Acts 7 gets confused between the stories of Abraham and Jacob, of Jacob and Joseph. But Stephen was under pressure, in the middle of a mob mentality, they were gnashing their teeth at him and he could not go into a verse-by-verse teaching with the 71 members of the Sanhedrin. So he telescoped them.143

Then Stephen began the longest speech in Acts, and he declared: Brothers, showing his solidarity with them, and fathers (not an uncommon name for the members of the Sanhedrin), showing his respect for them as leaders of the Jewish people, listen. Wasting no time in preliminaries, he plunged directly into his subject. The God of glory appeared to our father Abraham when he was in Mesopotamia, or Ur of the Chaldees (Genesis 15:7), before he lived in Haran (see the commentary on Genesis Dq – Terah Became the Father of Abram, Nahor and Haran). The point Stephen was trying to make here was that the divine Presence was not restricted to the land of Isra’el or the Temple because the Sh’khinah glory appeared long before there was a Tabernacle or a Temple, even before Abraham crossed over into the borders of the Promised Land. As a Diaspora Jew, he understood certain things that the native-born Jews did not.

Stephen repeated the content of the covenant and the call of Abraham, saying: Leave your country and your relatives, and come here to the land that I will show you (7:2-3). The context of what he is speaking about is Genesis 11:31 through 12:3. He also telescopes the events of Genesis 15:7. The first stage was that Abraham left the land of the Chaldeans and settled in Haran. From there, after his father died, God moved him to this Land where you now live. This divine command was, in fact, spoken in Haran. Since, however, it is clear from Genesis 15:7 that God called Abraham out of Ur, it can be reasonably assumed that the divine call came to him there before he lived in Haran. It would be natural to assume that the content of the divine message given at Ur was the same as that given in Haran, and hence, there is no need to speak of Stephen being in error.144

As Paul would do later (Romans 4 and Galatians 3), Stephen focused on Abraham as a man of faith. Completely obeying God’s sovereign call and left his homeland, not knowing exactly where he was going. Even after arriving in his new country God gave him no inheritance in it – not even a foothold – yet He promised “to give it to him as a possession to him and to his descendants after him,” even though he had no child (7:4-5). The closest Abraham came to seeing such a grand promise fulfilled was the birth of Isaac. What he did receive was a promise of Egyptian bondage.

But God spoke in this way, that his “descendants would be foreigners in a land belonging to others, and they would enslave and mistreat them for four hundred years (a rounded number for the sake of brevity, once again he was under a lot of pressure). But I will judge the nation they serve as slaves, God said: and afterward they shall come out and serve Me in this place (7:6-7). Luke quotes the TaNaKh almost always in a form either corresponding to the LXX or close to it, and not according to the Hebrew Masoretic Text. Here Genesis 15:13-14 is quoted close but not exactly corresponding to the LXX.145

Following the flow of salvation history, Stephen moved into the patriarchal period. Then God gave Abraham the covenant of circumcision. So he became the father of Isaac and circumcised him on the eighth day, and so Isaac with Jacob, and Jacob with the twelve patriarchs, the heads of the twelve tribes of Isra’el. For the sake of brevity, Stephen chose to bypass the stories of Isaac and Jacob and move directly to Joseph. The patriarchs became jealous of Joseph and sold him into Egypt. Yet God was with him. He rescued him out of all his troubles and granted him favor and wisdom before Pharaoh, king of Egypt, who made him governor over Egypt and all his household (7:8-10). Joseph’s revelation also came to him outside the Promised Land.

Stephen makes it extremely clear that the twelve patriarchs were guilty of opposing God and His purpose. They sold Joseph, but God rescued him. The nation’s rebellion against ADONAI began with the patriarchs themselves. The Sanhedrin was doing the very same thing that the founding fathers of the nation were guilty of doing and what they were falsely accusing Stephen of doing. Although he waits until the conclusion of his speech to openly declare that Yeshua is the Messiah, even in his historical summary, Stephen gives snap-shots of Messiah. There are eighty ways that the life of Joseph prepares us for, or foreshadows, the life of Christ (see the commentary on Genesis Iw – The Written Account of the Generation of Jacob).146

“Famine and great suffering came over all Egypt and Canaan, and our fathers could find no food. But when Jacob heard that there was grain in Egypt, he sent our fathers there the first time. On the second visit, Joseph made himself known to his brothers, and his family became known to Pharaoh. The one rejected by his brothers became the savior. The point Stephen was making, was that this was also true of the Messiah. So Joseph sent and called for Jacob and all his relatives – seventy-five persons (see the commentary on Genesis Km – Jacob’s Genealogy). Genesis 46:26-27; Exodus 1:5 and Deut 10:22 all say that seventy people went down to Egypt. However, the Septuagint text of Genesis 46:27 reads seventy-five. Stephen, being a Hellenist, would naturally have used the Septuagint figure. The larger figure was apparently arrived at by including the total of Joseph’s descendants born in Egypt. Jacob went down to Egypt and died, he and our fathers. They were carried to Shechem and laid in the tomb that Abraham had bought for a sum of money from the sons of Hamor in Shechem (7:11-16). Again, for the sake of brevity, Stephen telescopes the accounts of Abraham’s purchase of the Machpelah site and Jacob’s acquisition of the Shechem site. His purpose was not to recite history, but to establish that he was not guilty of blaspheming ADONAI.147

Moshe

Having successfully defended himself against the charge of blaspheming ADONAI, Stephen then moved to the second accusation, rejecting Moshe. But as the time drew near for God to fulfill His promise to Abraham, the people increased and multiplied in Egypt – until “there arose another king over Egypt who did not acknowledge (Hebrew: yada, which can be translated acknowledge) Joseph (Exodus 1:8).” Dealing with our people with cruel cunning, this king mistreated our fathers and forced them to abandon their infants so they would not survive. At this time Moses was born. The details of Moshe’s life and ministry were well known to the Sanhedrin, so Stephen merely summarized them to make his point. Sensitive to the accusation that he blasphemed Moshe, Stephen makes the point of praising him, describing him as extraordinary before God. For three months he was nurtured in his father’s house. And when he was set outside, Pharaoh’s daughter took him and raised him as her own son (see the commentary on Exodus Ak – A Man of the House of Levi Married a Levite Woman). Moses was educated in all the wisdom of the Egyptians, and he was powerful in his words and deeds (7:17-22). Moshe was a remarkable man. His natural leadership abilities, coupled with the most comprehensive education in the ancient world, made him uniquely qualified for the task that was ahead of him.

God’s call came when he was approaching forty years of age. At that time, it came into his heart to visit his brothers, Bnei-Yisrael. Although raised in Pharaoh’s household, Moshe had never forgotten his people. No doubt his mother instilled in him during the years ADONAI had providentially arranged that she serve as his nurse, that he was a Hebrew. So when he approached forty, he decided to help his long-suffering people. When he saw one of them being treated unjustly, he went to the defense of the oppressed man and avenged him by striking down the Egyptian. By taking that murderous action, he was assuming that his brothers understood that by his hand God was delivering them, but they did not understand and did not recognize him as the deliverer. The point Stephen was making was that the same thing would happen to the Messiah. So on the next day he appeared to them as they were fighting. He tried to reconcile them in shalom, saying: Men, you are brothers. Why do you wrong one another? But the one doing wrong to his neighbor pushed him away, saying ominously: Who appointed you ruler and judge over us? You don’t want to kill me as you killed the Egyptian yesterday, do you (Exodus 2:14). Realizing the killing of the Egyptian had become widely known Moses fled and became an exile in the land of Midian (see the commentary on Exodus Al – Moses Fled From Pharaoh and Went to Live in Midian), where he became the father of two sons, Gershom and Eliezer (7:23-29). No doubt viewing him as the leader of a Jewish rebellion, Pharaoh sought to unsuccessfully kill him (Exodus 2:15).

When forty years had passed (see the commentary on Exodus Am – Moses in Moses), and the time had come for Moshe to lead the Israelites to the Promised Land, the Angel of ADONAI appeared to him in the wilderness of Mount Sinai in the flame of a burning bush (see the commentary on Exodus Aq – Flames of fire from within a Burning Bush). Once again, Stephen’s point is that God revealed Himself outside of the Promised Land. When Moses saw it, he was amazed at the sight. But when he came up to look, there came the voice of Adonai: “I am the God of your fathers, the God of Abraham and Isaac and Jacob.” Moses trembled in fear and did not dare to look. But Adonai said to him, “Take the sandals off your feet, for the place where you are standing is holy ground (even though it was outside of the “Holy Land”). So anywhere that God appears is an area of holiness. God’s blessings were not limited to the Holy Land or to the Temple. I have surely seen the oppression of My people in Egypt and have heard their groaning, and I have come down to deliver them. Now come – let Me send you to Egypt” (7:30-34).

Then Stephen reached the climax of his defense of blaspheming Moshe. This Moses – whom they rejected, saying: Who appointed you as ruler and judge? – is the one whom God sent as both ruler and redeemer, by the hand of the Angel of ADONAI who appeared to him in the bush (7:35). You will notice in the next several verses that Stephen keeps emphasizing the word this. This Moses, or this man (meaning Moses), because Stephen wanted to drive the same point home over and over again. The very same person that Isra’el rejected, was the one same person that God used to bring Isra’el out of bondage. This is a constant pattern in Isra’el’s history – spiritual pride coupled with spiritual ignorance (which is a real bad combination) causes them to reject the deliverers God sends them. It has sometimes been pointed out that Yeshua could not have been the Anointed One, or else Isra’el would have recognized Him. But as Stephen points out, they rejected both Joseph and Moses. This was the typical response to those God sent to deliver them. Yeshua spoke of this attitude in Matthew 21:33-46.

Moshe accomplished his mission and led them out of Egypt. But Isra’el’s further rebellion against God and Moses, in spite of the wonders and signs they had already seen in the land of Egypt and in the parting of the Sea of Reeds and in the wilderness, caused them another delay. Because of that rebellion, they wandered outside the Promised Land for forty more years. It was obvious from Stephen’s speech that he had the utmost respect for Moses and the charge of blaspheming Moshe was as false as that of blaspheming ADONAI. The Jewish response to Moses, like their response to Joseph, paralleled their response to Messiah. Then Stephen reminded them that Moshe, in the well-known passage from Deuteronomy 18:15, predicted Messiah would come, prophesying: God will raise up for you a prophet like me from among your brothers (7:36-37). Thus, they were doing again what their fathers had done – rejecting the God-sent deliverer. Only this time it was more serious than all the others combined. This was the Messiah they were rejecting.148

Torah

It was an easy transition from Moshe to the Torah, since the two are so closely related. While Moses was with the community in the wilderness, he received the Torah from angels who spoke to him on Mount Sinai, and was with our fathers. He received living words of the Torah to pass on to us (7:38). Stephen affirmed the Torah again, making a “not guilty” plea. He declared that ADONAI was the author of the Torah, that the angels were its mediator Acts 7:53; Galatians 3:19; Hebrews 2:2), and Moses was the recipient. That certainly was not blasphemy, and the Sanhedrin knew it.

But now comes the turning point. Stephen commented how the original recipients of the Torah had failed to keep it. Our fathers, he reminded them, did not want to be obedient to him. It was not Stephen who disobeyed the Torah, but the very fathers that the Sanhedrin revered. Stephen did not reject Moshe, but those same fathers shoved him and the Torah aside and in their hearts they turned back to Egypt. Worse still, while Moses was on Mount Sinai receiving the Torah from God, the people turned to idolatry, saying to Aaron, “Make gods for us who will go before us. For this Moses who led us out of the land of Egypt – we have no idea what has happened to him.” Right from the moment when the Torah was given, they rebelled against it. For all their declarations of loyalty to the Torah and the Temple, and their accusations against Stephen, his hearers belonged to a nation, which right from the start, had rejected the Torah and the true worship of YHVH.

With this thought the speech takes a new turn, and down to verse 50 it is concerned with the twin themes of idolatry and Temple-worship in Isra’el. And they made a calf in those days, offered a sacrifice to the idol, and they kept on rejoicing in the works of their hands. That single act of idolatry, led to other acts of idolatry in the wilderness. So in the next two verses Stephen deals with Isra’el’s long history of idolatry throughout those forty years and beyond. Ha’Shem’s response was to give them up to idolatry. So in these two verses Stephen summarizes the remainder of Isra’el’s history and tendency toward idolatry that brought on the Babylonian Captivity (see the commentary on Jeremiah Gu – Seventy Years of Imperial Babylonian Rule).

So God turned and gave them over to serve the host of heaven, or star worship, just as it is written in the book of the Prophets (7:39-42a), that is, the book of the twelve minor prophets, regarded as a single book in the TaNaKh. To prove his point, Stephen quotes the book of Amos.

It was not to Me that you brought sacrifices and offerings, but to idols,

for forty years in the wilderness, was it, O House of Isra’el (7:42b LXX)?

You also took up the tent of Moloch, the Ammonite star god, connected to the planet Venus and similar to the Greek goddess Venus, to whom human sacrifices were offered,

and the star of your god Rephan, a Babylonian god associated with the planet Saturn, the images you made to worship. The sacrifices Isra’el offered were the Levitical sacrifices God commanded, but they diverted their sacrifices to these gods. The point Stephen was making was that the idolatry that began with the golden calf, ended up with the worship of the host of heaven, the stars. This is verified throughout the Scriptures (Deuteronomy 17:3; Second Kings 17:6, 21:3 and 5, 23:5; Second Chronicles 23:3 and 5; Jeremiah 13:15).

And I will deport you beyond Babylon’ (7:43 LXX). His point is that the prophets had already accused Isra’el idolatry, therefore his accusation was nothing new.

Luke quotes the TaNaKh almost always in a form either corresponding to the LXX or close to it, and not according to the Hebrew Masoretic Text. Here Amos 5:25-27 is quoted close but not exactly corresponding to the LXX.149

Temple

In response to the accusation that he spoke against the Temple, Stephen traced its history to show his great respect for it because YHVH ordained it. Our fathers had the Tent of Witness (the Tabernacle) in the wilderness, but this also was outside the Promised Land. Furthermore, just as the One speaking to Moses had directed him to make it according to the design he had seen. The wilderness generation could not plead ignorance of God’s glory, since the Tabernacle was in their midst. Nor could the later fathers who, having received it in turn and brought it in with Joshua when they took possession of the land of the nations that God drove out before our fathers. From the time of the conquest until the days of David, Isra’el had the Tabernacle, a constant symbol of God’s holy presence. Yet they persisted in falling into idolatry. After Ha’Shem gave David victory over all his enemies, he asked to find a dwelling place for the God of Jacob (Psalm 132:3-5 LXX). David’s request was denied, however, and it was Solomon who built a house for Him (7:44-47). Stephen makes only a brief reference to Solomon’s Temple, since the Sanhedrin was very familiar with its history. Moreover, the current Temple was not Solomon’s, which had been destroyed by the Babylonians. The current Temple had been built by the non-Jew Herod. So the transitory nature of the Tabernacle, and then the Temple lead to Stephen’s main point, namely that Elyon does not dwell in man-made houses. There can be no doubt that the Sh’khinah glory abided within the most holy place of the Tabernacle and later the Temple, but still did not limit Him in any way.

In contrast to this view Stephen stresses that ADONAI did not currently reside in the Tziyon Temple, God dwells in heaven, and furthermore, not only is God and God’s true dwelling not made with human hands, instead all the world and all that is in it is God-made. Nothing is wrong with the Temple nor with building it, but it is wrong to believe that it (and perhaps it alone) is God’s dwelling place. Furthermore, allegiance to a Temple built with human hands could place Isra’el in danger of repeating its earlier wilderness sin, for the golden calf had also been made by human hands.150 As the prophet says (7:48):

‘Heaven is My throne,

and the earth is the footstool of My feet.

What kind of house will you build for Me, says Adonai,

or what is the place of My rest (7:49)?

Did not My Hand make all these things’ (7:50)?

Luke quotes the TaNaKh almost always in a form either corresponding to the LXX or close to it, and not according to the Hebrew Masoretic Text. Here Isaiah 66:1-1 is quoted verbatim from the LXX with a change in the word order.151 Stephen was not guilty of blaspheming the Temple. They were, for confining Ha’Shem to it. Instead, with Isaiah, he argued that God was greater than any Temple. It was the symbol of God’s presence; not the prison of His essence.

Throughout Stephen’s speech the tension must have been building. As he pointed out Isra’el’s rejections and apostasies, the Sanhedrin grew increasingly uneasy. They must have wondered what point was he trying to make? They didn’t have to wait long. Having laid the historical foundation for it, he hit them with a devastating indictment: They were just like their fathers in the days of Joseph, Moses and David. They were stiff-necked, or obstinate, people (7:51a)! Because they prided themselves on their physical circumcision and ritual behavior. Stephen’s description of them as uncircumcised of heart (Leviticus 26:41; Deuteronomy 10:16, 30:6; Jeremiah 4:4, 9:26; Ezeki’el 44:7 and 9) and ears (Jeremiah 6:10) was very pointed! Their sin had never been forgiven. They were as unclean before God as uncircumcised Gentiles. That was the ultimate condemnation.

These are the TaNaKh’s characterization of Isra’el: God’s people outwardly bear the sign of the covenant with Abraham, but inwardly are impure and rebellious (Romans 2:17-3:2). You always resist the Ruach ha-Kodesh; just as your fathers did (Isaiah 63:10), you do as well. Which of the prophets did your fathers not persecute? They killed the ones who foretold the coming of the Righteous One. Yeshua made the same accusation (Matthew 23:29-36). Now you have become His betrayers and murderers, not directly, as they were about to do with Stephen, but through Pontius Pilate and the Roman government.152 You who received the Torah by direction of angels and did not keep it (7:51b-53)! They were without excuse, since the Torah pointed to Messiah (John 5:39). Stephen once again echoes the words of his Lord, who said to those same leaders: If you believed Moses, you would believe Me, for he wrote about me (John 5:39). There was no offer of salvation, only a declaration of disobedience.

Despite their proud boast that if we had lived in the days of our ancestors, we would not have taken part with them in shedding the blood of the prophets (Matthew 23:30), they had done far worse. Their fathers had murdered God’s prophets, they, however, had murdered His Son, the Righteous One. Now they were about to commit yet another murder. Stephen would shortly become another in the long line of ADONAI’s messengers killed by God’s chosen nation, and the first killed for preaching the name of Messiah.153

Leave A Comment