Y’honatan Helps David Escape

First Samuel 20: 1-24a

DIG: What did Y’honatan have to lose by helping David survive? In view of the risk, why did Y’honatan do it? How do you think Y’honatan felt upon hearing David’s anguish-filled complaint against his father? Who does Y’honatan prefer to trust at this point? Why? Which do you think angers Sha’ul more, David’s absence from the table, or his own son’s collusion with David? Why?

REFLECT: Have you ever had a friend that you would die for? Whose circumstances and emotions do you most readily identify with? Sha’ul, trying to preserve your own self-interests? David, trying to escape and torn by conflict of interests? Or Y’honatan, losing a loved one?

1016 BC

The fact that Sha’ul was out of action (to see clink click Ap – Sha’ul Tries to Kill David) gave David the opportunity to seek out Y’honatan, who had already been a successful mediator between Sha’ul and himself, and who might be able to do it again.70 In all of literature, David and Y’honatan stand out as examples of devoted friends. Y’honatan had the more difficult situation because he wanted to be loyal to his father while at the same time being a friend to the next king of Isra’el. Therefore, two themes are familiar to us in this study of the Life of David. First is the friendship of Y’honatan and David, and the second is David’s real fear of Sha’ul’s madness and his flight for his life. These two themes witness the hidden resolve of YHVH that Sha’ul should decrease and David should increase.71

David’s Consultation with Y’honatan: Then David fled from Naioth at Ramah while Sha’ul lay naked on the ground (First Samuel 19:24). And David, breathless, went to Y’honatan and passionately protested his innocence: What have I done? What is my crime? How have I wronged your father, that he is trying to kill me?” David needs the matter settled once and for all. Above all, David needs his friend to believe him. But Y’honatan was in denial. Sha’ul had thrown his javelin at David twice (18:10-11 and 19:9-10), he had sent three groups of soldiers to kill him without success, so finally the king went to Ramah himself to do the job (18:20-24). How much evidence did Y’honatan need? The prince thought that his relationship with his father was closer than it really was and that Sha’ul would confide in him; but subsequent events would prove him wrong for Sha’ul would eventually even try to kill his own son Y’honatan.

Y’honatan, a trusting son and loyal friend, protested to David, saying: “Never! You are not going to die! Y’honatan still ignorantly clung to his father’s oath in 19:6 that David would not die. Look, my father doesn’t do anything, great or small, without letting me know. Why would he hide this from me? It isn’t so!” Y’honatan refused to believe that Sha’ul had any deliberate design on David’s life, attributing all the evidence to the contrary to his fits of madness until it became painfully obvious to him (First Samuel 20:1-2 CJB).

But David took an oath and said: Your father knows very well that I have found favor in your eyes, and he has said to himself, “Y’honatan must not know this or he will be upset.” As surely as ADONAI lives, as surely as you are alive, there is only a step between death and me. Finally, Y’honatan begins to believe David and said: Anything you want me to do for you, I’ll do (First Samuel 20:3-4 CJB).

David devised a simple test to remove any doubts about the king’s intentions: David answered Y’honatan, “Look, tomorrow is Rosh Hashanah, and I ought to be dining with the king. This New Moon festival was a time when shofar’s sounded and many offerings were given (Numbers 10:10, 28:11-15; Psalm 81:3). This was the festive meal, and David’s presence was expected. Instead, let me go and hide myself in the countryside until evening of the third day when the festival would be over.

If your father misses me at all, say: David begged me to let him hurry to Beit-Lechem, his city; because it’s the annual sacrifice there for his whole family. If he says: “Very well,” then your servant will be all right. But if he gets angry, you will know that he has planned something evil. Therefore show kindness (see the commentary on Ruth Af – The Concept of Chesed) to your servant, for you bound your servant to yourself by a covenant before ADONAI. Y’honatan took the initiative to make this covenant, ADONAI being the witness. But if I have done something wrong, kill me yourself! Why turn me over to your father to be killed by him!

Y’honatan said: Never! Then Y’honatan reaffirms his covenantal promise: If I were to ever learn that my father had definitely decided to harm you, wouldn’t I tell you first? Then almost as an afterthought, David asked Y’honatan, “Who will tell me in the event that your father gives you a harsh answer?” Because it might have been neither possible nor safe for Y’honatan to do it himself. Then Y’honatan set the plan in motion. He said to David, “Come, let’s go out into the countryside where it is safe to talk.” So they both went out (First Samuel 20:5-11 CJB).

The Covenant: When they got there, Y’honatan said to David, “ADONAI, the God of Isra’el is my witness: After I have sounded out my father, about this time tomorrow, or the third day, then, if things look good for you, I will send a messenger and let you know. But if my father intends to do you harm, he will communicate with David personally. May ADONAI deal with me ever so severely, if I do not let you know and send you away in peace. May the LORD be with you, just as He used to be with my father (First Samuel 20:12-13 CJB).

Y’honatan went beyond the immediate crisis to deal with future events. When a new king came to power in the ancient world, it was expected that the family and supporters of the previous regime would be put to death. However, you are to show me ADONAI’s kindness not only while I am alive, so that I do not die; but also, after ADONAI has eliminated every one of your enemies from the face of the earth, you are to continue showing kindness to my family forever” (First Samuel 20:14-15 CJB). Y’honatan was fully aware that he had renounced his throne in favor of David and the possible implications of that action. The scenario feared by Y’honatan here is exactly what happened later in Second Samuel Chapters 3 and 4, but David would remember his oath to Y’honatan by honoring his son (see Da – David and Mephiboseth), and by sparing him from death (2 Samuel 21:7). It was the least David could do to fulfill his covenant commitment to his friend Y’honatan.

Y’honatan’s speech is terribly ironic. The voluntary commitment to sacrificial love is rare and deeply moving. In Y’honatan’s case it was accompanied by a naiveté regarding his own father. He failed to see that David represented any threat to his father and is accordingly reluctant to acknowledge that Sha’ul actually intended to harm David (First Samuel 20:1-7). When he invoked the LORD’s vengeance on David’s enemies, he didn’t realize he was talking about his own father!72

So Y’honatan made a covenant with the house of David, saying to him, “May ADONAI seek its fulfillment even though David’s enemies, which would include the house of Sha’ul. Y’honatan had David swear it again, because of the love he had for him (see First Samuel 18:1) – he loved him as he loved himself (First Samuel 20:16-17 CJB). This was reminiscent of the oath between Jacob and Laban (see the commentary on Genesis Hs – So Jacob Took a Stone and Set It Up as a Pillar and He Called It Galeed), meaning that YHVH would Himself avenge any breach of the covenant to which He had been a witness. Y’honatan was about 44 at the time and David was about 24.

These verses seem to ignore the immediate crisis of coping with the murderous Sha’ul. Here, he has no significant presence. It is the future of this friendship rooted in the covenant that matters. By Sha’ul’s absence, the narrative asserts that he is irrelevant to the future of both David and Y’honatan. David is a man of loyalty and will honor his commitment to Y’honatan. That leaves the future secure.73

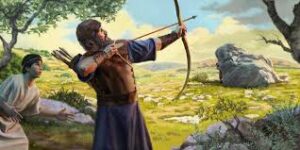

The Sign Between David and Y’honatan: Y’honatan said to him, “Tomorrow is Rosh-Chodesh, and you will be missed, because your seat will be empty. The third day, hide yourself well in the same place as you did before; stay by the Stone of Departure. The rabbis teach this is a “sign-stone” that was an unmistakable place where the sling of the arrows could be safely performed. I will shoot three arrows to one side, as if I were shooting at a target. Then I will send a young boy to recover them. If I tell the boy, ‘They’re here on this side of the Stone, take them,’ then come because it means that everything is peaceful for you; as ADONAI lives, there’s nothing wrong. But if I tell the boy, ‘The arrows are out there beyond the Stone,’ too far to retrieve, then go back home, because ADONAI is sending you away. The sign was prearranged in case Y’honatan was being watched and found direct communication with David dangerous. As for the matter we discussed earlier, ADONAI is between you and me forever.” So David hid himself in the countryside, clearly agreeing with the plan (First Samuel 20:18-24a CJB).

Like Y’honatan and David, believers today are to guide our way through life’s challenges by the compass of faithfulness to our covenant duties. Few of us face death when the leader of our country changes, but we do confront various difficult challenges in life. My mother took care of my ailing father for many, many years at the end of his life. She had promised faithfulness “in sickness and in health” and her duty to him was neither glamorous nor dramatic, but covenantal. We could cite other examples, a husband remaining faithful to his difficult wife, believers keeping a business which makes only a small profit, church members pulling together during a pastoral transition, or in other cases messianic believers taking a costly stand for ADONAI’s Word despite the scorn of civic leaders and friends.74

Leave A Comment