At – God’s Claim to the Best of Life 7: 22-27

God’s Claim to the Best of Life

7: 22-27

God’s claim to the best of life DIG: Why did the worshiper offer the fat of his or her sacrifice? What did Cain and Abel have to do with this? What would cause a believer to be cut off from the community today (see Hebrews Cz – God Disciplines His Children)?

REFLECT: Fat represents the best, pointing to the quality of what is given to God? Are you giving the best of what you are and what you have to ADONAI right now? What might you be holding back? What is the solution? How can you help others to give their best?

God lays claim to the life of His people and the best that they have.

At the heart of the Torah is the prohibition of eating that which belonged to ADONAI, the fat and the blood. That a separate section at the end of the five offerings makes this point, especially after the shalamim offering (to see link click As – The Shalamim Offering), which involved eating, is evidence of the importance of the reminder. Fat represents the best, pointing to the quality of what is given to God. It has to be the best. Blood is life, and so the blood belongs to YHVH because our life is in His hands. The sanctity of life and the special use of the blood in the Tabernacle were safeguarded by this prohibition.

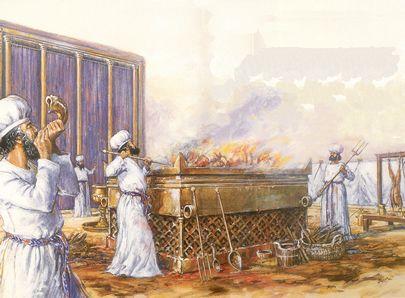

God’s people must acknowledge that the best belongs to Him (7:22-25): The fat in the TaNaKh was considered symbolic of the best portion. A worshiper presented a fat animal for sacrifice because it was the best of his flock. This clearly means that many times the word fat refers to more than what we would consider the actual fat; it could refer to the best portions of the healthiest animals. The concept was first introduced in the narrative of Cain and Abel. Abel brought the fattest of the firstborn of the flock to ADONAI (Genesis 4:4). This was the best he had.

Rather than gain a good price at the market, the devout worshiper saved the best for the LORD. And even then, the actual fat of the animal was designated as God’s – no doubt a symbolic gesture that what represented the best and the healthiest was given to YHVH. To eat the fat was an encroachment on divine property.83

ADONAI said to Moshe, “Say to the people of Isra’el, ‘You are not to eat the fat of bulls, sheep or goats. The fat of animals that die of themselves or are killed by wild animals may be used for any other purpose, but under no circumstances are you to eat it. For whoever eats the fat of animals of the kind used in presenting an offering made by fire to ADONAI will be cut off from his people’ (7:22-25).” Only these specific fats were holy and were forbidden to be eaten. Even if an animal was not a sacrifice, those fats were forbidden. However, the entrail-fats of kosher animals not designated for sacrifice (for example, deer, bison and giraffes) were permissible.

The commandment to avoid the forbidden fats is meant to remind us of our worship of ADONAI. Just as we set aside a day of our week to worship the LORD, we set a portion of our income for the work of the Kingdom (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Do – When You Give to the Needy, Do Not Do It to be Honored by Others: seven principles of scriptural giving). Today, observant Messianic believers and religious Jews buy their meats from a kosher butcher because they don’t know what fats are ground into the beef at the grocery store.84 Meat that has not been bled to death is considered to have blood still in it. Thus, animals that die of causes other than slaughter are forbidden by the Torah.

God’s people must acknowledge that their life belongs to Him (7:26-27): The blood was also to be given to the LORD. As with fat, no one could eat blood; both elements were exclusively ADONAI’s. If fat represented the best, and the blood represented life – the essential part of the animal. God put His claim on these elements: He demanded them for His own exclusive possession. To take and eat them plundered what was holy (Deuteronomy 12:23).

The violator of this prohibition was cut off. Here too we remember Paul’s mention of a premature death for those who treat the LORD’s table with contempt (see the commentary on First Corinthians Cb – The Answer: Honor the Body). Great holiness mixed with fear (Proverbs 9:10) needs to go with sacrificial worship; the portions of the sacrifice set apart for God must be treated accordingly. You are not to eat any kind of blood, whether from birds or animals, in any of your homes. Whoever eats any blood will be cut off from his people. The point being made here is that God lays claim to the life of his people and the best they have. In ancient Isra’el, the offering symbolized their acknowledgment of this. To eat fat or blood denied God of His rightful claim. Hence, the punishment was severe.

We know what this section meant in the theology of the worship system in the Dispensation of Torah (see the commentary on Exodus Da – The Dispensation of the Torah). But what about today? Application can be made in two areas. First, one may apply this passage by discussing the nature of giving to ADONAI in worship. This idea may be expressed this way: God requires nothing short of the best, the essential things of our lives.

To understand the basis for this, one must recall the Torah, specifically Deuteronomy, was the covenant relationship between Isra’el and her great King (see the commentary on Deuteronomy Ah – Treaty of the Great King). God had a right for what He was commanding. But we must remember that the animal was a substitute representing the worshiper. So the call is for us to give our best to ADONAI, the best of our time and talents, our possessions – our very lives. That is what we must give to God. The degree to which we do this reflects the degree of our commitment.

When we offer ourselves, the Lord wants our best – healthy in body (as much as He allows) and mind, developed spiritually mature, conformed into the image of Messiah (see the commentary on Romans Cl – Our Bodies and Redemption). YHVH will use anyone, of course, but He desires that what is given to Him be carefully prepared – a good gift. Too often, believers give to the LORD useless, worn-out materials, the leftovers of time and money, or a halfhearted gift. Or some may sincerely offer themselves, but balk at the demands of growing in grace and truth (John 1:14). The simple truth from Isra’el’s sacrificial system is this: God demands the best we have to offer; and genuine faith goes out of its way to give the best to ADONAI, whatever it is.

Dear Heavenly Father, Praise and thank You for the joy of relationship with You. You are a wonderful Father! The great depth of Your mercy and grace is shown by Yeshua’s painful sacrifice as the Lamb of God (John 1:29). In Him we have redemption through His blood -the removal of trespasses – in keeping with the richness of His grace (Ephesians 1:7). I want to thank You with my love. I would say thanks so much if someone ran out ahead of me and saved my life from a car swerving madly down the street; but I am much more thankful for Your eternal salvation. You planned to adopt me as Your child from before the creation of the world (Ephesians 1:4). You knew what extreme pain and suffering You would go thru, and still you willingly went thru with it. For the joy set before Him, He endured the cross, disregarding its shame; and He has taken His seat at the right hand of the throne of God (Hebrews 12:2c).

I rejoice in serving You with all my heart, even when that brings me pain, emotional and physical. For our trouble, light and momentary, is producing for us an eternal weight of glory far beyond all comparison (Second Corinthians 4:17). I know that my life on earth will soon be over and I will have the great joy of living with You in heaven for all eternity! I love pleasing You! In Yeshua’s holy name and power of His resurrection. Amen

Secondly, we may also apply this passage by viewing Messiah as a type. If fat represents the best, then certainly Yeshua was the best of the flock – He was the lamb without blemish, healthy and whole, ready to be the pleasing sacrifice to God the Father. Moreover, His blood was sacrificed for the sins of the world. The blood is the essential part of the atonement. His perfect sinless blood . . . that is His life, satisfied every claim of YHVH’s holiness and justice so that He is free to act on behalf of sinners.

Nothing else can be offered to God for atonement – especially not an inferior offering like the works of righteousness that sinful creatures bring. We must guard this point very strongly as the absolute center of our faith, the basic doctrine of the Church, made up of the Jewish and Gentile believers (Ephesians 2:14). The body and blood of Yeshua is the holy sacrifice, pleasing to God. His shed blood provides the atonement for sin. Nothing short of this satisfies the demands of a righteous God; nothing other than His precious blood can redeem. Therefore, to treat the blood of Messiah as ordinary, to treat His death as common or as martyrdom and not the perfect sacrifice, defies the revelation from God. Defiling the sacrifice of Messiah or trampling on it as if it means nothing will bring judgment from God.

The question of eating blood became an issue in the early Messianic community when Gentiles, who had not treated the Torah as their blueprint for living, came to faith in Messiah. In a ruling designed to preserve the unity of the growing Church and not offend Jewish believers, the leaders of the Council at Jerusalem said that Gentiles should abstain from blood (see the commentary on Acts Bt – The Council’s Letter to the Gentile Believers). There was no theological reason to retain the ancient mitzvot once the fulfillment had come in Messiah. But to eat the Lord’s Supper unworthily, to treat the cup of the B’rit Chadashah as a pagan festival, was a sin worthy of premature death, of being cut off from the congregation.85