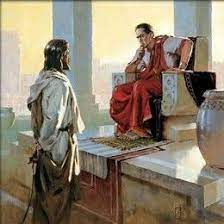

Jesus Before Pilate

Matthew 27:2, 11-14; Mark 15:1b-5; Luke 23:1-7; John 18:28-38

About 6:00 am Friday morning, the fifteenth of Nisan

Jesus before Pilate DIG: What was Pilate’s overriding concern in this trial? What insights into Pilate and Jesus’ character do these scriptures offer? Or the procurator’s conscience? What new charge does Caiaphas and the Great Sanhedrin bring against Messiah? Why was He silent before His accusers?

REFLECT: What is truth to you? Without Jesus, all truth is relative. You are a ship without a rudder? Do you have a morale compass? Why? Why not? Do you believe in situation ethics? Since both Peter and Pilate “caved in” under pressure, why do we tend to scorn Pilate but honor Kefa? Isn’t that pretty hypocritical? Do you see any of Pilate’s qualities in you? Do you want to change? How can you change?

The pale grey light had passed into that of early morning and Yerushalayim was just waking up. Judas had already come before Pilate before midnight and presented the official charge so that the Roman cohort could be released for Yeshua’s arrest.

Pontus Pilate was in the City of David. He normally resided seventy miles (113 km) northwest of Jerusalem in Caesarea on the Mediterranean Sea, but his presence was always required in the City at times like this. So when visiting Yerushalayim, Pilate occupied the official residence of the procurator, called the praetorium, which had been the palace of Herod the Great. Pilate was a personal friend of Lucius Sejanus, during Emperor Tiberius’ extended retirement on his lavish villa on the isle of Capri. Sejanus had earned the emperor’s trust by transforming a small regiment of the imperial bodyguard into the Praetorian Guard, a kind of secret police force that became an influential factor in Roman politics. Furthermore, Sejanus shrewdly eliminated all of his political rivals through slick maneuvering and violent intrigue. One of the rivals he destroyed was none other than Drusus, the emperor’s own son, whom he slowly poisoned with the help of the unfortunate man’s wife.

With Drusus dead of seemingly natural causes, Sejanus enjoyed ruling as the de facto leader of Rome, and he saw to it that his friend Pontius Pilate received one of the most coveted posts in the empire: procurator of Judea. While extremely challenging, the post offered unlimited potential for political greatness in the empire. Sejanus wanted a strong ruler to keep Judea peacefully subservient, despite the Jews’ mounting discontent.

The historian Philo of Alexandria describes the procurator as “ a man of very inflexible disposition, and very merciless as well as very obstinate.” Pilate’s inflexibility had served him well in the past, but it nearly became his undoing in Judea. Where he brought brute force, finesse was required. He failed to understand the delicate balance between autonomy and control needed to govern Jews. Soon after taking command from his headquarters in Caesarea-by-the-Sea, Pilate sent a clear message to Jerusalem, letting the Israelites know he was in charge. Normally, the procurator’s army wintered in Caesarea, but Pilate ordered his soldiers to spend the winter in the City of David. Not only that, but he ordered them to bear Caesar’s image on their shields and to display it in key locations throughout the Holy City. He had determined that Tziyon should be treated like all other conquered nations. But this, of course, violated the Torah which said: Watch yourselves very carefully, so that you do not become corrupt and make for yourselves an idol, an image of any shape, whether formed like a man or a woman (Deuteronomy 4: 15-16).

Before long, a large delegation of members from the Great Sanhedrin (to see link click Lg – The Great Sanhedrin), marched en masse to Caesarea to protest. The resulting standoff became a test of wills. For Pilate to remove the images would be a humiliating show of weakness, yet keeping the peace was his sole responsibility. The Jewish leaders refused to go home until the images were removed, which prompted Pilate to respond with brute force. The Jewish historian Josephus described the procurator’s means of breaking the stalemate.1545

“On the sixth day of the protest he ordered his soldiers to have their weapons hidden while he came and sat on his judgment seat. It was so prepared in the open place of the city that it concealed the army that lay ready to oppress [the Jews]. And when the Jews petitioned him again, he gave a signal to the soldiers to encompass around them, and threatened that their punishment should be no less than immediate death unless they stopped bothering him and go home. But they threw themselves onto the ground, and laid their necks bare, and said they would rather die than that the wisdom of their laws should be violated. Pilate was deeply affected by their firm resolution to keep their laws inviolable. So he commanded the images to be carried back from Jerusalem to Caesarea.”1546

Then the Jewish leaders rose from their illegal trial in the Royal Stoa, bound the Suffering Servant and led Him to the palace of the Roman governor Pilate. Caiaphas demanded an immediate audience with Pilate. He stood outside the double gates with Jesus, the disguised Temple guard, and the at least a quorum of the Great Sanhedrin. By now it was early morning, and they did not enter the praetorium because it would defile them and they wouldn’t be allowed to celebrate the Passover (Matthew 27:2; Mark 15:1b; Luke 23:1; John 18:28 NLT). The festive offering, or the Chagigah, was offered at 9:00 am on Passover. Ironically, it was a peace offering, which they had to offer undefiled. Therefore, here we see the strangest contradiction. They who had not hesitated in breaking every commandment of God and every law of their own making (see Lh – The Laws of the Great Sanhedrin Regarding Trials), would not enter the praetorium least they should defile themselves and be unable to participate in the Chagigah offering.1547 Consequently, Caiaphas requested that the governor come down to the double gates where the two had met earlier that morning. He knew that Pilate would understand.

It took a while to wake the Roman governor up, to tell him about the Jewish assembly outside, and for him to dress and make his way down to the gate. But once he got there, he could not have been very pleased to see a large crowd, extravagantly dressed Sadducees, plainly dressed Pharisees and a prisoner who had clearly been beaten up.1548

So Pilate came out to them. This is the first time he came down the steps. A servant brought out a regal chair and the procurator walked down the right-hand stairway and, five steps up from the praetorium, sat on a chair that was placed on a stone landing. Jesus saw through swollen, purple eyes. His wrists were tied behind His back and a rope was tied around His neck. He stood alone, in front of the mob, and Pontius Pilate looked at the Nazarene for the first time, as Yeshua, for the first time, looked at Cesar’s governor.

What each one saw was hardly earth-shattering. The Messiah looked at the Roman and saw a short, patrician-looking man of about fifty years of age. He appeared to be nervous. His eyes shifting from side to side, swinging quickly to anything or anyone that moved. His hair was graying and he wore an expensive toga and gilded sandals. Pilate stared at Jesus and saw a rather average looking Jew with puffed lips and discolored cheeks. There were flecks of blood on His robe. He was dirty. Behind the Nazarene, the Procurator saw Caiaphas, some of the ranking priests, deferential, but still uneasy in the presence of Gentiles. And behind them, people jammed the arches, some even hanging from the wall-bracket lamps.

Pontius Pilate held his right hand aloft. In a few seconds, the babbling of the crowd subsided. A tribune marched forward from the rear of the court, followed by four legionaries and took his post by the side of the prisoner. The Temple guards dropped back. From now on, the disposition of this case of the Meshiach versus pharisaic Judaism was squarely in the iron fist of Rome. What charges are you bringing against this man, asked the Roman governor loudly (John 18:29)? He pointed to Yeshua.

Caiaphas appeared to be shocked at Pilate’s question. The high priest had been there early that morning to discuss the case with the Procurator, to explain to him the seriousness of the matter in its relation to Jewish law. Not only that, but the Temple guard knew that the tribune who had led the raiding detachment to Gethsemane had surely returned and briefed Pilate on everything that had gone on there. Why, then, this pretense of no knowledge of the renegade Rabbi?

The priests exchanged uneasy glances. This could mean that the cruel oppressor was ready to have Jesus tried before him – and, in that case, might dismiss the charges against Him for lack of evidence. Outside, Pilate’s question was passed on to the gathering crowds, who roared so much that Caiaphas had to wait for silence before he answered. If He were not a criminal, they replied: we would not have handed Him over to you (John 18:30).

Take Him yourselves, shouted Pilate, standing and preparing to leave, and judge Him by your own law (John 18:31a). With no accusation there would be no condemnation, and with no condemnation there would be no sentence. Ultimately, the Great Sanhedrin was successful in having the Romans execute Yeshua, but Pilot had the last laugh. He used these very charges to infuriate the Jews with the sign that he had placed above the head of Jesus on the cross: THIS IS JESUS, KING OF THE JEWS. They asked him to take it down, but he would not (Matthew 27:37; Mark 15:26; Luke 23:38; John 19:19-22).

He knew, of course, that the Great Sanhedrin had already tried this blasphemer and had condemned him to death, but the coldly angry procurator was determined to have the final say in this semantic swordplay. To bring the high priest to his knees, symbolically, all Pilate had to do was to pretend innocence of the entire matter and walk off the scene.

But several of the priests cupped their hands together and shouted together: We have no right to execute anyone (John 18:31b). They did not say that they had no power to condemn a prisoner to death; only that they could not carry out their own sentence. This took place to fulfill what Jesus had said about the kind of death he was going to die (John 18:32). The Mishna and the Talmud, commentaries on the TaNaKh, tell us the exact date that the Romans took away the death penalty from the Great Sanhedrin. It was 40 years before the destruction of the Temple in 70 AD. Thus, 30 AD, the very year of this trial, the Roman government took away the right to enact the death penalty by stoning. This demonstrates the providence of God. It shows He made sure that Jesus would die by crucifixion. Because the Jews would never have crucified Him, they would have stoned Him to death. And if they had stoned Him, there would not have been any atonement for sin.1549

Caiaphas had dreaded that moment. Though he wanted the Romans to execute Yeshua, the charge of blasphemy was a Jewish offense and the Romans couldn’t care less about it. Not only that, Pilate could hardly tolerate Jews and was not about to risk his career by allowing Jewish laws determine whom he crucified.1550

The governor did not answer. He turned his back on the priests and started to walk up the steps inside his quarters in the praetorium. The accusers were dismayed. It looked as though the hearing was over. The crowd of disguised Temple guards were stunned! One of the ranking priests shouted: We caught this man subverting our nation (not true). He opposes the paying of taxes to Caesar (not true), and passes Himself off as the Messiah (true), a king (true) (Matthew 22:21; Luke 23:2). They took their religious charge against Christ and turned it into a political charge.

Halfway up the steps to his quarters, the procurator paused and looked around. He pulled his long toga up off the stones and thought about what he had just heard. The idea of a Messiah wouldn’t have bothered the Romans too much, but the idea of a king meant opposition to Rome – someone other than Caesar as their king. The last thing Pilate needed was a Jewish rebellion. Really, all three charges had their roots in sedition. Therefore, the Jewish leaders attempted to force Pilate to sentence Jesus without a witness because they couldn’t seem to find Judas anywhere.

Pontius Pilate studied the little knot of priests and was forced to show a brief smile of admiration. They had rid themselves of Yeshua as a local problem and had thrown Him to the procurator as a menace to the Empire. Pilate could hardly put himself in the position of defending Jesus. That was not his job. He was the highest judge and the top administrator of the country. However, there was still a little room for maneuver. Not much. Just a little.

He summoned a servant to go out into the courtyard and tell the tribune to bring Jesus to him in his quarters. The prisoner was brought in and stood in the center of the room. Pilate studied him carefully. But there was nothing to see except a pathetic figure of a man, stripped of his dignity. Pilate looked at his staff of officers . . . they just shrugged.

Once an accusation was made, the defendant was interrogated. This was his opportunity to tell his side of the story. Pilate asked Yeshua the pertinent question, presumably because he already knew the official charge against Him. It’s likely that the procurator had witnessed Messiah’s triumphal entry just days earlier. He wanted to know if the Nazarene was, in fact, in the process of overthrowing the government in Judea.1551 The governor stood up and walked over to Yeshua and asked Him, “Are you the king of the Jews?” Pilate wants to know if Jesus was a competitor to Cesar. The words are yours, Christ replied (Matthew 27:11b; Mark 15:2b; Luke 23:3a; John 18:33). While this response might seem a bit evasive to some, it was really the most fitting to answer his question. To merely say “yes” would imply that Messiah sought an earthly Kingdom at that time. To say “no” would deny the fact that He is, in reality, the KING of kings and LORD of lords (Revelation 19:16). Yeshua’s answer covered both interpretations of the question; in essence, He is the King of Isra’el but not in the sense that Pilate could understand.1552

The swollen lips began to move. Are you asking this on your own, Jesus inquired, or have other people told you about Me? The words do not convey the intended shadings of meaning. What Jesus really meant was this, “Did you, as a Roman governor, observe Me acting as king of the Jews or have others told you about My spiritual Kingdom?” Pilate misunderstood the interrogative reply and stood before the Messiah and asked: Am I a Jew? The Gentiles in the room howled with laughter. Your own nation and high priest have handed you over to me. What have you done (Matthew 27:11b; John 18:34-35 CJB)? The tone now was soft and sympathetic. The procurator looked at the prisoner hopefully. All he needed was a denial. He knew that Jesus had not pretended to be the temporal king of the Jews and had not aspired to it. He also knew the story about the coin with Caesar’s image, because he had spies everywhere. He knew that self-preservation is critical to all human beings and he was giving the Nazarene the chance to save His life.

My Kingdom, Jesus said slowly, almost as though He was selecting the words with special care, is not of this world. It was as if Yeshua was saying, “I’m not a competitor to Cesar.” Then He offered simple proof of this. If it were, My servants would fight to prevent My arrest by the Jewish leaders. But My Kingdom is not of this world (John 18:36 NLT). This is not to say that the messianic Kingdom and the Lord’s rule is only “spiritual,” not to be expressed really and physically in this world, fulfilling the prophecy that Isra’el will become the head and not the tail (Deuteronomy 28:13); but that the present aspect of His Kingdom is in the hearts and lives of believers, not in international politics (which was the basis of Pilate’s question). Therefore, Christ, without denying His office as the Messiah, claimed that He was no threat to Rome and could not be condemned on a charge of treason.1553

Unhappiness on earth cultivates a hunger for heaven. By gracing us with a deep dissatisfaction, God holds our attention. The only tragedy, then, is to be satisfied prematurely. To settle for earth. To be content in a strange land . . . We are not happy here because we are not supposed to be happy here. We are like foreigners and strangers in this world (First Peter 2:11). And you will never be completely happy on earth simply because you were not made for earth. Oh, you will have your moments of joy. You will catch glimpses of light. You will know moments or even days of peace. But they simply do not compare with the joy that lies ahead.1554

Pilate was annoyed with the foolishness of the pious faker. He said: You are a king, then! He wanted to know if Jesus was a king in any sense. Our Savior answered saying: You say that I AM a king. In fact, the reason I was born and came into the world is to testify to the truth. Everyone on the side of truth listens to Me (John 18:37). The days of guessing and groping and half-truths are gone. Jesus came to tell us the truth. That is one of the great reasons why we must either accept or reject Yeshua Messiah. There is no halfway house about the truth. We either accept it or reject it. Christ is the truth.1555

Pontius Pilate drew himself up to his full height. His lips were curled with scorn and he snapped: What is truth (John 18:38a)? The problem was he was looking right at the Truth, but didn’t recognize Him. And many people still ask that question today. Many have become disillusioned with life because they don’t recognize the existence of truth. In the absence of solid, basic truth, we are adrift on a churning sea of ideas with no compass to tell us which way to go. But Jesus taught there this is truth. Not only that, He made the bold claim: I AM the way and the truth and the life (John 14:6). Yeshua presented Pilate with a choice – the same choice He offers us – compromise truth and advance your status in the kingdom of Tiberias, or walk in the light of truth and receive unseen glory in God’s Kingdom.1556

With this . . . the governor motioned for the soldiers to take the prisoner back outside to the Jews gathered there (John 18:38b). The soldiers and Jesus led the way, followed by Pilate and his officers. The crowds at the twin gates watched tensely as the procurator came all the way down the steps for the second time and across the courtyard of the praetorium to a point in front of Caiaphas and the Sadducees. A servant carried the Roman curule chair and placed it behind him. It was a special chair on which the Roman governor sat when he was about to render a judgment.

The people watched, almost breathlessly, as Pilate sat. The Messiah stood at his right side and some of the soldiers stood between the judgment chair and the crowd with their swords drawn. The governor wasted no time and announced to the Sadducees and the crowd, “I find no basis for a charge against this man” (Luke 23:4; John 18:38c). There was a moment of stunned silence, and then a riotous roar resounded from the crowd. Caiaphas and the other priests repeatedly struck their foreheads and turned to the people in mute appeal with their arms extended to the heavens and their mouths open wide. The snarl of the crowd grew louder. Some of the off-duty soldiers ran into the garrison room and retrieved their body armor and swords and ran to the praetorium. This is the first declaration of innocence. There will be others.

Pilate sat. He smiled a small smile as he looked at the frenzied faces. Caiaphas and the others of the Sanhedrin knew that he was turning Jesus loose to confound them. The Lord looked out at the mob under the arches and all the eyes He saw were on fire with hatred for Him. God the Son was not alone; however, because God the Father and God the Spirit were with Him. The soldiers began to make threatening gestures. The crowd quieted.

However, the Sadducees and the elders were not satisfied. They wanted the troublemaking Rabbi dead, so they accused Him of many other things. But He gave no answer. So again Pilate asked Him, “Aren’t You going to answer? Don’t you hear the testimony they are bringing against You?” But Jesus still made no reply, not even to a single charge – to the great amazement of the governor (Matthew 27:12-14; Mark 15:3-5). Yeshua was not going to answer those charges. Caiaphas and the Great Sanhedrin had invented a political charge to disguise the real source of their fury . . . the Nazarene claimed to be the long awaited Messiah, but did not believe in the Oral Law (see Ei – The Oral Law)! And yet He was performing miracles, so they claimed He was demon possessed (see Ek – It is only by Beelzebub, the Prince of Demons, that This Fellow Drives Out Demons). Since the procurator had already declared His innocence and the Sanhedrin had already declared His guilt, there was no reason for the Lord to answer any accusations.

But the Jewish leadership kept on insisting. They bowed formally and said: He stirs up the people, pointing to them, all over Judea by his teaching. He started in Galilee and has come all the way here. On hearing this, the governor, who had been listening with annoyance, suddenly grabbed the arms of the curule chair and sat up. He had forgotten that the prisoner originally came from the north. Pontius Pilate began to look pleased.

Pilate asked if the prisoner was a Galilean (Luke 23:5-6). Certainly, the priests said. Everybody who knew this mocker of God was aware that He came from the little town called Nazareth. Indeed, His name was Jesus of Nazareth, son of Joseph the carpenter. This gave Pilate the opportunity to get off the hook because Herod Antipas was in Jerusalem for the Passover. Therefore, the Roman governor refused to accept custody of Yeshua. When he learned that Jesus was under Herod’s jurisdiction and just a short distance away at that time (Luke 23:7), he said, “Well then, this is not my case to decide. It should be under the jurisdiction of Herod, Tetrarch of Galilee . . . send Him to Herod.”1557

Leave A Comment