Paul’s Message in Lystra

14: 8-20a

47 AD

Paul’s message in Lystra DIG: What was religious life like in Lystra? Compare verses 8-13 with 3:1-11. How are the two stories alike and different? What results from each healing? What does Paul emphasize about ADONAI in his message? How is his speech to this crowd in verses 15-17, different from his sermon in the synagogue in 13:17-41? Why? Since Pisidian Antioch was 100 miles away, what does that tell you about the nature of Paul’s opposition? After reading verses 19-20, how would you characterize Paul? His supporters?

REFLECT: What does the difference between Paul’s speech in 13:17-41 and his speech in verses 15-17 teach you about sharing your faith with various types of people? How do people understand the gospel through their own prejudices and beliefs? How do you typically handle complements and success? Do they sort of go to your head? What usually happens when we depend on others’ positive opinions to feed our pride? When you think of the most humble, sincere people you know, what qualities of theirs are the most admirable – the ones you’d most like to possess yourself?

Do you ever wonder why God doesn’t perform miraculous works more often? Have you thought, “Just one good miracle would really turn things around.” If so, consider what happened here. Paul and Barnabas proceeded to the city of Lystra where Paul met and healed a man who had been crippled from birth. Because of the miracle, the crowd thought Paul and Barnabas were gods. Not exactly the outcome they desired!311

Lystra was a region in the province of Galatia, about eighteen miles southwest of Iconium, in the center of Asia Minor. It was a small mountain rural town, off the major route. Its main significance was a Roman military post, and for the reason it had been given the status of a colony in 6 BC. A Roman military road connected it with the other colony city in the region, Pisidian Antioch, 100 miles or so to the northwest. This was the first of three visits Paul made to this city, and what an eventual one it was! On his Second Missionary Journey, Paul enlisted Timothy in Lystra (16:1-5), and he made a visit to this church on his Third Missionary Journey as well (18:23).312 The significance of the story of what happened in Lystra is that for the first time in Acts, missionaries came to a town where there was no synagogue, and Jews play no apparent part in the story. Thus, new methods were needed because now they were trying to reach pagan Gentiles with no Jewish background. Therefore, the events in Lystra prepare us for the debate in Chapter 15 (to see link click Bs – The Counsel at Jerusalem).313

The healing of a cripple: The narrative begins with a miracle story. Paul and Barnabas fled to the Lycaonian cities of Lystra and Derbe and the surrounding countryside. Now a man was sitting in Lystra without strength in his feet, lame from birth, who had never walked. To authenticate his gospel message, Paul had been given the same authority to perform miracles that Yeshua had (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Cs – Jesus Heals a Man at the Pool of Bethesda). In fact, this was the same situation that Peter confronted earlier in the book (see Ap – Peter Heals a Lame Beggar). This man overheard Paul speaking (Greek: lalountos, meaning ordinary conversation). It is likely that Paul was simply speaking with some of the citizens in the marketplace, telling them about the Good News of Yeshua, and the crippled man overheard what he said (14:8-9a). The word produced faith, “So faith comes by hearing, and hearing by the word of God” (Romans 10:17), and faith brought healing.314 When Paul looked intently at him and saw that he had faith in Messiah to be healed. How could Paul see this man’s faith? Obviously ADONAI gave him the gift of discernment to minister to that man.

Then Paul said with a loud voice, which would attract the attention of the others, “Stand right up! On your feet!” And the man leaped up and began to walk around (14:9b-10)! The story is brief and to the point without further elaboration, only containing the basic elements of an ancient miracle story (description of the illness, interaction with the healer, proof of the healing, and the reaction of the crowd or audience). The healing represents the first display of Paul’s miraculous powers and has many features in common with Peter’s healing of Aeneas (9:32-35) and particularly with his healing of the lame man. Like the latter, this man had been lame from birth. Also like the man at the Beautiful Gate, this man leaped up and walked about when healed. There is no mention of the name of Yeshua or the power of God, but the reader of Acts has had sufficient examples by now to know that it is indeed through the divine power that the miracle was worked (3:16, 4:30, 9:34). The people of Lystra, however, did not know that, and this ignorance led them to the wrong reaction.315

The excited crowd declared Paul and Barnabas to be gods: It is difficult not to read this story in light of a famous myth recorded fifty years earlier by the Latin poet Ovid, in his book Metamorphoses 8.626ff. In the legend, the supreme god Jupiter (Zeus to the Greeks) and his son Mercury (Hermes to the Greeks) once visited the Lycaonian hill country, disguised as mortal men. In their disguise they decided to test the hospitality of humans. Posing as poor travelers, they sought hospitality but were turned down a thousand times. At last, however, they were offered lodging in a tiny cottage, thatched with straw and reeds from the marsh. Here lived an elderly peasant couple called Philemon and Baucis, who entertained them in spite of their poverty. They offered their guests all their food and wine. Though it was not much, Baucis and Philemon explain that they are content with what they have because they love each other. Eventually, the gods revealed themselves. They destroyed by flood all the homes that would not take them in, but spared Baucis and Philemon. Consequently, when the people of Lystra saw this unique miracle of Paul healing the lame man from birth, they assumed that Zeus and Hermes had come down again. And because they did not want to be destroyed again with a flood, they immediately began to sacrifice to these two men. Apart from the literary evidence in Ovid, two inscriptions and a stone altar have been discovered near Lystra, which indicate that Zeus and Hermes were worshiped together as local patron deities.316

Paul spoke Greek, and apparently the crippled man and the crowd knew enough Greek to get the gist of what he was saying. However, the Lycaonian language was a native tongue, a language Paul himself did not know. The crowd, apparently familiar with the myth that Ovid wrote (see above), assumed that once again “the gods” have come to us in human form.317

The pagans acknowledged the miracle but attributed it neither to ADONAI, of whom they knew nothing, nor to the Adversary, as did the Sanhedrin with Yeshua (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Ek – It is only by Beelzebub, the Prince of Demons, That This Fellow Drives Out Demons), but to false gods. Now the crowd, seeing what Paul had done, lifted up their voices, saying in Lycaonian, “The gods have become like men and come down to us!” Since it was in the Lycaonian language that the people shouted out their belief that the gods had visited them again, it is understandable that the missionaries did not at first understand what was happening.318 And they began calling Barnabas “Zeus” and Paul “Hermes” (because he was the main speaker). Zeus was the supreme head of all the pagan deities. Hermes was a son of Zeus and the messenger of all the gods. Hence, he was the god of persuasiveness. These two deities were supposed to travel together. As a result, the people, having decided that Paul, by his persuasiveness, must be Hermes, inferred that his traveling companion must be Zeus.319 This was the reason Barnabas was listed first (14:11-12).

It only dawned on them when the priest of Zeus (whose job it was to keep the gods happy), whose temple was before the front gate of the city, brought bulls and garlands; he wanted to offer a sacrifice with the people (14:13). Only the best for visiting gods! It was customary to build shrines to their deities and to set up their images before the city gates. These images were crowned with garlands of cypress, pine or other leaves, or of flowers. The garlands were sometimes placed upon the altars, and then upon the priests. This shows that although Lystra was within the Greek and Roman world and culture, they were still very pagan.

Paul appealed to the crowd, asking them to worship the true God: But the apostles didn’t realize what the priest of Zeus was doing until someone who spoke Greek interpreted it for them. Then they tore their clothes and rushed out among the crowd. Paul’s solution was to identify God as the source of the blessings they had experienced, and to point out that for that reason ADONAI alone is to be worshiped. This is Paul’s first message to a pagan audience. Crying out, he declared: Men, why are you doing these things? We too are human, just like you! We proclaim the Good News to you, telling you to turn from these worthless, powerless idols that create nothing, to the living God (14:14-15a).

If you want God to use you, you must know who God is and know who you are. Many believers, especially leaders, forget the second truth. We’re only human! If it takes a crisis to get you to admit this, God won’t hesitate to allow it, because He loves you. And one more all of us need to remember along with Paul, “I delight in weakness, in insults, in distress, in persecutions, in calamities. For when I am weak, then I am strong (Second Corinthians 12:10).320

Paul’s message was not based on the TaNaKh, because this was a pagan audience. Therefore he started with the witness of God in creation (Romans 1:18-23). He made it clear that there is but one God who is the living God, the giving God, and the forgiving God. He had been patient with them, not judging them for their sins as they deserve.321 Paul began with the point that He is the God of creation, the One who made the heaven and the earth and the sea and all that is in them. In past generations He removed His grace from the Gentiles and allowed all the nations to go their own ways (Romans 1:24-32). There was a tolerance of God’s part toward sinners who did not have the full revelation of His holy will. Those times ended with the coming of Messiah (4:12). Yet He did not leave Himself without a witness – He did good things by giving you rain from heaven filling your hearts with joy and gladness. In Greek mythology Zeus was the god of rain, but then Paul told them it was the living God of Isra’el that provided them with the rain. Furthermore, God gave them fruitful seasons. In Greek mythology Hermes was the god of giving of food, but again, Paul told them it was the God of Isra’el. Even saying these things, they barely restrained the crowd from sacrificing to them (14:15b-18). At this point Paul didn’t mention Messiah because his purpose in Lystra was not to preach the gospel per se, but to stop the pagans from worshiping idols.322

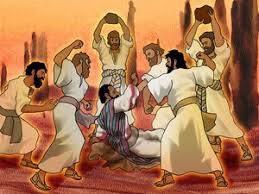

Not surprisingly, the pattern of resistance increased again: We all know that people can be incredibly fickle. One minute we are laying palm branches in the road, crying: Hosanna in the highest. The next minute we are crying: Crucify Him, or I never knew Him. So it was with the adoring crowd at Lystra. One minute they were preparing to worship Paul and Barnabas; however, just as the crowd settled down, some Judaizers (see the commentary on Galatians Ag – Who Were the Judaizers), unbelievers claiming to follow Yeshua, came from Pisidian Antioch and Iconium. We now see that the Jewish opposition to Paul and the gospel is more organized. The stoning which had been plotted in Iconium (14:5), now took place. They traveled 100 miles or so to oppose Paul and Barnabas’ ministry in Lystra. Embarrassed and feeling foolish, the Lystran crowd was an easy target for the clever enemies of the Truth who used the confusion to create a riot. The attack focused on Paul, since he was the main speaker.323 And after they won the crowd over they stoned Paul (Second Corinthians 11:25; Second Timothy 3:11) and dragged him out of the city, supposing him to be dead (14:19). As the stones were hurled at him, did Paul remember Stephen’s radiant face and perhaps even pray Stephen’s prayer (7:59-60)? The Judaizers who were pursuing Paul ironically parallel the actions of Sha’ul going to Damascus to take believers into custody (9:1-2). Later Paul would say: I bear in my body the marks of Yeshua (Galatians 6:17), he may have had in mind the scars from this incident.

Supposing is from the Greek word nomizo, which usually means to suppose something is not true. Nomizo appears in Acts 7:25, where Moses wrongly supposed the Israelites would understand that God had sent him to deliver them. In Acts 8:20, it describes Simon the sorcerer’s false assumption that he could buy the power of the Ruach ha-Kodesh. Nomizo is used in Acts 16:27 to describe the Philippian jailer’s nearly fatal supposition that the prisoners had escaped. Paul was not dead; he merely laid there unconscious. The fact that the visiting Jews merely suppose that Paul was dead suggests that this was not an official execution, but a lynching.

But the mission’s ministry to Lystra had not been without fruit, and some of the disciples they had made surrounded the battered, unconscious body of the fallen emissary. His would-be executioners believed Paul to be dead and left after they contemptuously dumped his body outside the city, but the Gentile believers had stayed behind, either to take his body away for a decent burial or to protect it from further harm. One of those disciples was Timothy (16:1), and possibly his mother Eunice, and grandmother Lois (Second Timothy 1:5). And while they were deciding what they should do, miraculously, Paul got up under his own strength and went back into the city (14:20a). A miracle in itself. Why did he go back into the city? To prove he wasn’t intimidated. He was not only resilient; he was courageous. The very next day he did indeed leave, but he left on his own terms.

Leave A Comment