Paul’s Advice from Jacob

and the Elders at Jerusalem

21: 17-26

57 AD

Paul’s advice from Jacob and the elders at Jerusalem DIG: What pressures do Jacob and the elders face as Paul comes to Jerusalem? How might Paul’s teaching cause those of the circumcision to be upset? This issue was supposedly settled at least six years earlier (see Chapter 15). Why do these tensions still plague Jerusalem believers? How would Jacob’s suggestion to Paul solve the problem for both of them? Why remind Paul’s Gentile companions what to do (see 15:20)? How does Paul’s action in verses 24-26 square with his view of grace and the Torah (see 20:24 and First Corinthians 9:10-20)?

REFLECT: How do you decide when you should use your freedom in Messiah and bend for the sake of others, and when you should stand for your principles? What are some of the first things to go through your mind when your good intentions are misunderstood? When was the last time you were stuck in the middle of a situation involving believers on both sides? What was the problem, and how did it work out? How difficult is it for you to seek common ground with unbelievers without compromising your faith? What are the struggles inherent in this juggling act? How do you find the balancing act?

Paul returned to Jerusalem during a very turbulent time, when political feelings were preparing to boil over. If one cannot say things were already quite violent by 58 AD, they were certainly quite volatile, and anything perceived to threaten the purity of the holy Temple, such as bringing a Gentile past the middle wall of separation (see below), would be reacted to with great passion and possibly with violence.497 Josephus described this period as a time of intense Jewish nationalism and political unrest. One insurrection after another arose to challenge their Roman overlords, but Governor Felix had brutally suppressed them all. This only increased the Jewish hatred for Rome and inflamed anti-Gentile sentiments.

Considering this political environment, Paul’s mission to the Gentiles would not have been well received, and this put the Jerusalem elders in a difficult position. On the one hand they had supported Paul’s witness to the Gentiles at the Jerusalem Council (to see link click Bt – The Council’s Letter to the Gentile Believers). But now they found Paul’s mission discredited not only among the Jewish populace (whom they were seeking to reach), but also among their most recent converts. The elders did not want to reject Paul. Indeed, they praised God for his success.498 Nevertheless, they needed to be careful how to handle his return.

The arrival: When we arrived in Jerusalem, the brothers and sisters welcomed us gladly (see Bx – Paul’s Vision of the Man of Macedonia: A closer look at the “us” or “we” passages and sea passages). There were reservations, however, and these quickly unfolded the next day. Paul went in with us to Jacob and all the elders of the Messianic community in Jerusalem were present. They were more than willing to meet with the representatives of the Gentile churches (20:4). Jacob, or James, was the half-brother of Jesus, spokesman, and the leading elder. They all probably went to his home. After greeting them, Paul reported to them in great detail what God had done among the Gentiles after three missionary journeys. And when the elders heard, they began glorifying God. They were overjoyed that so many Gentiles had been saved, but Paul’s success had created some problems for them. As Jacob explained: You see, brother, how many tens-of-thousands (or a minimum of twenty-thousand Jewish believers in Jerusalem alone not counting the rest of the country) there are among the Jewish people who have believed – and they are zealous for the Torah. They saw no contradiction in their faith in Yeshua and their zealousness for the Torah (21:17-20).

And so it is today. Messianic Jews today regard themselves as loyal Jews. Most have increased their Jewish consciousness as a result of coming to trust in the Jewish Messiah, and most are actively concerned for preserving the Jewish people. The idea in the Church that when one believes in Yeshua one leaves the Jewish people is false and misleading. There is no grounds for it in the New Covenant, which time and again demonstrates exactly the opposite. Christians who spread the lie that Jewish believers in Yeshua are no longer Jewish do incalculable harm to the gospel, to the Jewish people and to the Church – not the least of which by leading credibility to unbelieving Jews who have their own defensive reasons for holding the same view.

The lie: These zealots for the Torah have been told about you. Jews from the Diaspora likely were the ones who spread the reports among the Jerusalem believers that Paul taught all the Jewish people among the Gentiles to forsake Moses, telling them not to circumcise their children or to walk according to their ancestral traditions. The accusation against Paul, then, was that he was a traitor to the Jewish people who taught all over the Diaspora to stop functioning as Jews. Actually Paul was teaching just the opposite (Acts 16:3; First Corinthians 7:18 and 9:20). What’s to be done then? It was as if Jacob was saying, “How shall we deal with this situation where people are so misinformed and feelings run so high. No doubt they will hear that you have come” (21:21-22).499

We all know what it means to be misunderstood. You try to do the right thing, the godly thing, and you get criticized by other believers. Or even worse they gossip about you. It just drains your energy and excitement. Have you ever thought, “I expected this kind of thing from unbelievers, but I wasn’t expecting this from my brothers and sisters in the faith?” If so, you are part of a large fraternity, with Paul as a charter member. And as far as Paul was concerned what they were saying wasn’t even true. He had never told Jewish believers not to circumcise their boys. He told them not to insist that Gentile believers circumcise theirs! He was trying to make the point that circumcision had nothing to do with salvation.500

To correct this false interpretation of Paul’s ministry the elders said: Therefore, do what we tell you (they had obviously thought this through beforehand). We have four men who have taken a Nazarite vow on themselves (21:23). The law of the Nazirite was regulated in detail (Numbers 6:1-21). According to these decrees of the Torah every Israelite could specially dedicate themselves to ADONAI by a vow. During the period of this special dedication one was not permitted to consume wine, vinegar, or any other alcoholic drink. Furthermore, one was also not allowed to eat fresh or dried grapes. The Nazirite thus demonstrated that he was prepared to do without the Creator’s gifts, which are good in themselves – so long as they are not abused.

As a sign of the unlimited devotion to YHVH, the hair might not be cut even a little. Long hair had the same significance a woman’s veil in the worship service (First Corinthians 11:2-15): separation and dedication. The picture of the veil can be beautifully illustrated by the love story between Isaac and Rebecca. When Rebecca saw her future husband for the first time, she veiled herself (Genesis 24:65). By that she wanted to demonstrate to him: I am withdrawing myself from the glances of all men in order to be exclusively yours. The Nazirite, with his uncut hair, declared in symbolic language, “I am reserved for God!”501

The usual length of the Nazirite vow was thirty days.502, although Sampson (Judges 16:17), Samuel (First Samuel 1:11), and John the Immerser (Luke 1:15) were Nazirites for life. Paul had not started any Nazirite vow himself and the four men’s vow would expire in seven days. As their sponsor, Paul could participate in the ceremony marking the culmination of the four men’s Nazirite vows by going through the last seven days with them. But before he could do that he would have to purify himself and undergo a ritual bath (Hebrew: mikveh).503 So the elders told him, “Take them with you and purify yourself along with them and pay their and your own expenses, so that they may shave their heads.”

In addition, Paul also had to buy a year-old lamb, as well as two young doves as sacrifices, for each of the four men. The lamb was intended as a guilt offering (see the commentary on Exodus Fd – The Guilt Offering). One dove was to be presented as a burnt offering (see the commentary on Exodus Fe – The Burnt Offering), and the other as a sin offering (see the commentary on Exodus Fc – The Sin Offering). Furthermore, according to the Torah’s commands the purification by the ashes of a red heifer were in addition to this (Hebrews Bx – The Insufficiency of the Blood of Bulls and Goats).504 While these involved blood offerings, not all blood offerings were for atonement purposes. And the blood offerings for the completion of a Nazarite vow were not atonement offerings.

Displaying humility and a desire for unity, Paul agreed to the elder’s proposal. Doing so would not compromise biblical truth since, as Paul himself would write about in Romans 14 and 15, such matters were issues of our liberty in Messiah (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Dg – The Completion of the Torah). However, paying for himself and four others would be very expensive and would demonstrate that he took the Torah seriously, and that the charges against him were false. Jacob continued: That way, all will realize there is nothing to the things they have been told about you, but that you yourself walk in an orderly manner, keeping the Torah (21:24, also see 23:6 and 26:5). The authority of Jacob stood behind the declaration that Paul was Torah observant.

To complete a Nazarite vow, the four [Jewish] men would go to one of the four chambers in the corners of the Court of the Women  called the Chamber of the Nazirites, where they would cut their hair and solemnly burn it, along with a Peace Offering (see the commentary on Exodus Fg – The Peace Offering), on a special fireplace as a symbol of their dedication ADONAI (Numbers 6:13-20).505

called the Chamber of the Nazirites, where they would cut their hair and solemnly burn it, along with a Peace Offering (see the commentary on Exodus Fg – The Peace Offering), on a special fireplace as a symbol of their dedication ADONAI (Numbers 6:13-20).505

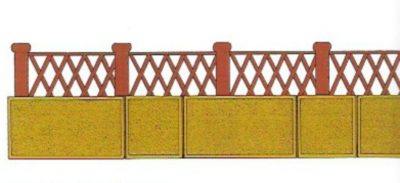

But to get to the Court of the Women, they had to pass through the middle wall of separation (Ephesians 2:14). Both Jews and Gentiles were permitted to enter the Temple Compound in order to approach the Golden Sanctuary, the dwelling place of the Eternal One. Yet after some dozen meters they came to a barrier. It consisted on a low wall of 75cm (or 2.46 feet) upon which a wooden lattice of 52.5 cm (1 foot 8.67 inches) was secured for a total of 127.5 cm. In rabbinical literature this barrier is referred to with the Hebrew word soreg (meaning a fence, a grill, or netting). The middle wall of separation was deliberately built low and furnished with lattice allowing a view through so that no one, not even a child, might be prevented from seeing the glorious view of the golden Sanctuary.

But this middle wall was the complete separation between Jews and Gentiles. No Gentile was allowed to go beyond this barrier, not even the God-fearers or Proselytes at the Gate – this “gate,” this middle wall separation (see Bb – An Ethiopian Asks about Isaiah 53). If, however, a heathen (in the sense of being a non-Jew) converted to Judaism and became a Proselyte of the Covenant, then the separation was lifted because they were no longer considered a heathen, but a Jew.

How complete the separation between Jews and heathens was can be deduced from the stone inscription that was placed at various intervals along the middle wall of separation. The texts on these tablets (57 by 86 cm) threatened the death sentence in Latin and Greek to every Gentile crossing the barrier. Even though the Romans had taken the death penalty away from Isra’el in 6 AD, there was still one exception. If a Gentile disregarded the middle wall of separation, he would be immediately executed, even if he were a Roman citizen. The tablet read: No foreigner may enter with the barricade that surrounds the Sanctuary and enclosure. Anyone who is caught doing so will have himself to blame for his ensuring death.506 Paul would later explain that Messiah is our shalom, the One who made the two (Jews and Gentiles) into one (Church) and broke down this middle wall of separation (Ephesians 2:14a).

Then the Jerusalem elders summarized the din (Hebrew for ruling, or a halakhic decision) of Acts 15. As for Gentiles who have believed, however, we have written by letter what we decided (see Bt – The Counsel’s Letter to the Gentile Believers) – for them to abstain from what is offered to idols, and from blood, and from what is strangled, and from immorality (21:25). So, Jacob reaffirmed Gentile freedom from the Torah, and he wanted Paul to reaffirm the freedom of Jewish believers to keep the Torah.

Like Messianic Jews today, Paul didn’t believe that he had to give up being Jewish when he accepted Messiah as his Lord and Savior. He was free to participate in Jewish worship and ritual as long as it was considered nonessential for salvation (First Corinthians 9:20). As a result, the next day Paul took the men, purifying himself in a ritual bath along with them. He went into the Temple compound announcing when the days of purification would be completed (six days from then) and also brought the sacrifices that would be offered for each one of them (21:26). Paul was required to undergo a seven-day purification as a result of being defiled by Gentile-land impurity (Numbers 19). Unlike the completion of his vow, the initiation of it apparently brought no controversy.

In the final analysis, what we see here is Paul being asked to act with cultural sensitivity to the Jewish context he found himself in, without compromising the gospel. Both Jacob and Paul demonstrated a generous spirit towards each other. On his part, Paul was quite willing to do so for the sake of unity it would create. Oftentimes, we may be asked, in ministry or in a given community, to engage in neutral practices that are culturally driven, not because we have to, but because it may prevent an unnecessary distraction of sharing the gospel, or doing damage to the unity of the congregations of God.507

Sometimes, Lord, it is not an enemy taunting me – otherwise I could bear it; it is not

a foe who rises up against me – otherwise I could hide from him. But it is one who is my peer, my companion and close friend. We used to have a close relationship, even fellowship. We walked together into the house of God. His buttery words are smooth

as silk, but war is in his heart. His words are softer than oil, but they are like drawn swords. As for me, I will cast my burden on You, Lord, knowing that You will support me; You will never allow the righteous to be shaken (Psalm 55:12-14, 22-23).

May I be true to You though others are false to me.508

Leave A Comment