Paul’s Witness before Caesar

27:1 to 28:16

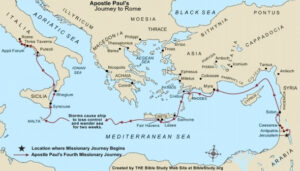

Seasonal data suggest the journey to Rome took place in late 59

during the risky time for sea travel, and the Paul probably arrived in Rome

at least by the early February 60 AD.

What was different about Paul’s voyage to Rome? In the final two chapters of Acts, all the major themes of the book come together. Not least among these is the journey motif. From the time the church at Antioch first commissioned Paul and Barnabas, the apostle had constantly been seen as traveling – to Cyprus, the towns of southern Galatia, to Asia Minor, Macedonia, Greece, Ephesus. Three times he made the return trip to Yerushalayim. Now he departed Palestine, seemingly for the last time, bound for the capital of the empire and his appearance before Caesar. He and his companions traveled this time by sea. Paul had traveled by sea before, and Luke had often depicted these voyages in extreme detail, naming ports and landmarks and even time spent sailing. But this voyage was different. It is told with considerably more detail, occupying three-fourths of the total text of Chapters 27 and 28.604 This account of Paul’s journey to Rome is considered on the finest ancient descriptions of any sea voyage.

Did Paul ever stand before Caesar in Rome? The overarching theme of the voyage is the providence of God. The central verse is 27:24 where the angel of God spoke to Paul and said, “Do not fear, you must stand before Caesar; and indeed, God has granted safety to you all who are sailing with you.” Paul’s witness in Rome had been the central focus since he resolved in the Ruach . . . to go to Rome (19:21). While imprisoned in Jerusalem, the Lord assured him in a vision that he would surely witness in the Roman city (23:11). Now, in the midst of the howling storm, Paul was given a final assurance that in God’s providence the witness before Caesar would take place. It is perhaps the major theme of Acts – the triumphful witness of Yeshua Messiah!605

Did the apostle ever appear before Caesar? Some have contended that probably he didn’t. It is surmised that his accusers from Judea never showed up to press their case, so the charges were dropped. There is no evidence for this view, and it runs counter to the testimony of the angel who informed Paul, “You must stand before Caesar” (Acts 27:24).

Was Peter ever in Rome? According to Roman Catholic tradition, Peter was the first bishop of Rome. His pontificate supposedly lasted for twenty-five years until he was martyred in Rome in 67 AD. The remarkable thing, however, about Peter’s alleged reign as pope in Rome, is that the New Covenant does not say one single word about it. The word Rome appears only nine times in the Bible, and never is Kefa mentioned in connection with it. There is no mention to Rome in either of Peter’s letters. But Paul’s journey to Rome is recorded in great detail in Acts 27 and 28. In fact, there is no evidence in the New Covenant, nor any historical proof of any kind, that Peter was ever in Rome.

Moreover, the most compelling reason for believing that Peter was never in Rome is found in Paul’s letter to the Romans! According to Roman Catholic tradition, Kefa reigned as pope in Rome from 42 to 67 AD. It is generally agreed that Paul’s letter to the church in Rome was written in the year 58 AD, at the very height of Peter’s alleged reign there. He did not address his letter to Peter, as he should have if he was pope, but to the believers in Rome. How strange for a missionary to write to a church and not mention its pastor! That would have been an inexcusable insult. What would we think of a missionary today who would dare to write a congregation in a distant city and without mentioning their pastor, tell them that he was anxious to go there so that he might bare some fruit among them even as he had seen in his own community (Romans 1:13), that he was anxious to instruct and strengthen them, and that he was anxious to preach to gospel there where it had not been preached before? How would the pastor feel if he knew that such greetings had been sent to 27 of his most prominent members, but not him? Would he stand for such unethical actions? Even more so the pope! If Peter had been ministering in the church at Rome for 16 years, why did Paul write to the people of the church in these words: I long to see you so that I may impart to you some spiritual gift to make you strong (Romans 1:11). Would that not be an insult to Kefa? Would it not be presumptuous for Paul to go over the head of the pope? And if Peter had been there for 16 years, why was it necessary for Paul to go there at all, especially since in his letter he says that he does not build on another’s foundation: it has always been my ambition to preach the gospel where Christ was not known, so that I would not be building on someone else’s foundation (Romans 15:20). At the conclusion of his letter to the Roman church, Paul sends greetings to the 27 people mentioned above, including some women. But he does not mention Kefa at all.

And again, had Peter been pope in Rome prior to, or at the time Paul arrived there as a prisoner in 61 AD, Paul could not have failed to mention him, for in the letters written in Rome during his imprisonment – Ephesians, Philippians, Colossians and Philemon – he gives quite a list of his fellow-workers in Rome and Peter’s name is not among them. He spent two whole years there as a prisoner and welcomed all who came to see him (Acts 28:30).

Nor does he mention Peter in his second letter to Timothy, which was written form Rome during his second imprisonment, in 67 AD, the year that Peter is alleged to have suffered martyrdom in Rome, and shortly before his own death (Second Timothy 4:6-8). He says that all his friends had abandoned him, and that only Luke was with him (Second Timothy 4:10-11). Where was Peter? If he was the pope in Rome when Paul was a prisoner, why did Peter not call on Paul and offer aid? What kind of spiritual leader would that be?

All of this makes it quite clear that Peter was never in Rome at all, even though the Vatican has publicly unveiled a handful of bone fragments purportedly belonging to him. Not one of the early church fathers gives any support to the belief that Peter was bishop in Rome until Jerome in the fifth century. Du Pin, a Roman Catholic historian, acknowledges “the primacy of Peter is not recorded by the early church writers, Justin Martyr (139 AD), Irenaeus (178 AD), Clement of Alexandria (190 AD), or others of the most ancient fathers.” Catholicism builds her foundation neither on biblical teaching, nor upon the facts of history, but like the Oral Law, only on the unfounded traditions of men (Mark 7:8).606

Leave A Comment