Historical Details Related to

First Kings 12:1 to 16:34

Four issues need special consideration. First, the division of the division of the nation into two parts has had a tremendous impact of the history of Isra’el. As Paul House relates in his commentary on First Kings, the separate entities never regained the prestige David and Solomon had established. They were also less able to fend off foreign invaders. Of course, First Kings 11:1-40 discusses the religious roots of the breakup. The Bible also notes that Jeroboam, a northerner, was already a likely candidate to take Solomon’s place. His position was supervisor over a forced labor project (11:27-28) underscored why northern Isra’el were tired of Solomon’s policies. They were drafted to work in the south, their tax burden was heavier than Judah’s and their love for the Davidic dynasty was always tenuous at best. Only spiritual commitments would keep the nation united, and those commitments had already been weakened by Solomon.

Second, because of the division of Solomon’s kingdom, other nations moved in against Judah and Isr’ael. That Pharaoh Shishak of Egypt favored Jeroboam meant that Solomon’s trade pact with Egypt was no longer valid. In fact, in Rehoboam’s fifth year Shishak attacked Judah with such force that the only payment of tribute induced him to withdraw (1 Kings 14:25-28). This invasion also greatly diminished the Isra’el-Egypt trade alliance. Egypt’s era of submissive weakness was over. To make matters worse, smaller nations rebelled against their former masters. Syria became impossible for Isra’el to control and soon became a threat in the north. Judah could not hold neither Ammon nor Philistia, and only Mo’ab continued to pay tribute. Each part of the divided kingdom had to face the future with less income from trade, with more external threats from countries small and large, and with turmoil between each other, a difficult future lay ahead.

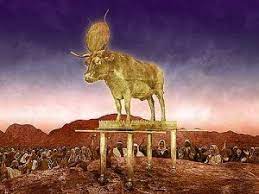

Third, Jeroboam’s apostate religion made covenant keeping even more difficult than it had been. Jeroboam was clever enough to realize that if his subjects traveled to Jerusalem for the religious festivals their loyalty might revert back to the house of David (First Kings 12:26-27). Therefore, he set up shrines in Dan on the extreme northern border and a more significant one at Bethel on his southern boundary. Jerusalem’s uniqueness in God’s sight was ignored. Jeroboam also set up golden calves to represent God’s presence in the new sanctuaries (to see link click Dd – Golden Calves at Bethel and Dan). Those images quickly became used as idols (First Kings 12:30), thus shattering the first two of the Ten Words (see the commentary on Deuteronomy Bk – The Ten Words). New priests were appointed who were not Levites (First Kings 12:31), and he changed the date of the feast of Booths from the seventh month to the eighth month (First Kings 12:33). Jeroboam’s changes were a compromise between Canaanite idolatry and traditional Judaism. Such syncretism led to loyalty to neither tradition. Ultimately, this false religion sapped Isra’el’s spiritual fiber to the extent that they did not have enough character to endure as a nation.

Fourth, the prophetic movement began to have more importance in both kingdoms. Ahijah, the prophet who declared Jeroboam’s rise to power in Chapter 11 returns in First Kings 14:1-8 to denounce Jeroboam and predict the end of the king’s dynasty. Unnamed prophets reaffirm God’s sovereignty over kings and governments in Chapter 13. Given the tension that already existed between monarchs and prophets, greater conflicts in the future appeared to be inevitable.323

Leave A Comment