Paul Sails to Rome

27: 1-11

Late 59 AD

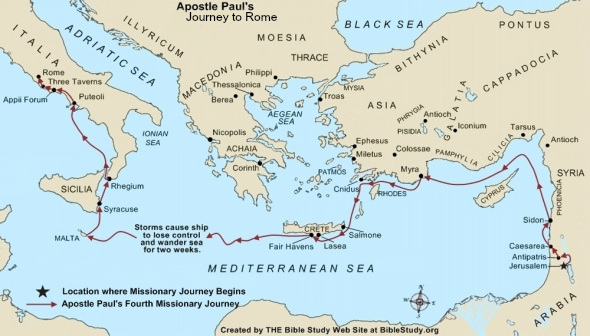

Paul Sails to Rome DIG: As Paul sets sail for Rome (see the map on Cz – Paul’s Journey to Rome), what points of interest can you locate along the way from Paul’s diary? From verses 1-3 and 43, what do you know about the centurion in charge? How does his concern for Paul indicate how Paul used his time while imprisoned in Caesarea? If you were the ship’s owner or navigator, how would you react to Paul’s warning about the 50-mile trip they wanted to make in verse 10? Would you have responded any differently than Julius did to Paul’s concern? Why? Why not?

REFLECT: When have you sailed off on a voyage where you were unprepared? What did you learn? How have you been about to help others from making the same mistakes that you did? Perhaps you’re dealing with an issue right now where you can’t get others to cooperate or agree with your advice and suggestions. How does this have you feeling? How have you responded? How have you been harmed by another person’s errors, whether deliberate or accidental? What has this done to your relationship? How are you handling your anger or regret?

From the perspective of Luke’s purposes as a historian and theologian, one is somewhat at a loss to explain the detailed treatment of this voyage. It does little to advance knowledge of the spread of the gospel. There are still theological points to be made and will be noted. The greater part of the story, however, doesn’t focus on theology, but rather concentrates on the voyage itself. Luke relates in delightful detail the threat of the storm and the narrow escape from death at sea.

But that is exactly through this extensive presentation of the story itself that the full theological impact is conveyed. Luke was at his literary best in this account, building up suspense in his dramatic portrayal of the violence of the storm, and the description of the sailors, the abandonment of all hope. At each point, however, when the situation seemed most desperate, there came a word of encouragement from Paul – his God would not abandon them . . . take heart, eat, be of good cheer. Then the final deliverance came. All were saved. Paul’s God had indeed not abandoned them to the anger of the seas. One cannot miss the emphasis on the divine providence of God, and it is precisely through the detailed telling of the story that the lesson has it greatest impact. It is “narrative theology” at its best.607

The journey from Caesarea to Crete: When it was decided that we should sail for Italy, they handed Paul and some other prisoners over to a centurion named Julius, one of the ten centurions of the Augustan Cohort (27:1; to see link click Bx – Paul’s Vision of the Man of Macedonia: A closer look at the “us” or “we” passages and sea passages). Evidently Luke stayed in Caesarea the whole time that Paul was detained there and would then accompany him to Rome. This is why he could offer such detail when writing the book of Acts. He may have also written the gospel of Luke while he was there for two years. He would have had easy access to Jerusalem to gather all the information he needed. There were two ships involved between the start of the journey and the shipwreck (see Dc – The Shipwreck at Malta), and this was the first.

Since all vessels were cargo ships in the ancient world, travelers seeking passage were in the habit of going down to the waterfront and searching until they found a ship scheduled to sail in the direction they wished to take. So we boarded a ship from Adramyttium, which was about to sail to the ports along the coast of Asia (27:2a). In all likelihood the vessel was privately owned, and passage was available to any who could pay. Sailing schedules were not only determined by favorable winds but also according to superstitions that plagued Roman soldiers. The Roman religious calendar prohibited sailing on ill-omened days such as August 24th, October 5th, and November 8th, the end of the month also being generally regarded as a dangerous time to be on the water. Having tentatively set a date, the ship’s officers would offer a pre-sailing sacrifice. If all the initial omens proved “positive,” sailing could still be delayed by such petty omens as a sneeze on boarding, a crow or magpie croaking in the rigging, or dreams. While the weather lasted, for example, no traveler was permitted to cut his hair or nails, although if it turned bad, nail clippings and locks of hair tossed into the sea as an appeasement offering. Blasphemy was completely forbidden, even if written in a letter carried abroad, and the body of anyone who died at sea was immediately thrown overboard, death on board constituting the worst possible omen.608

Adramyttium, its homeport, was located on the northwest coast of Asia Minor, south of Troas. Julius was probably hoping to find a larger ship bound for Rome as it stopped at the ports along the coast back to Adramyttium. From Asia Minor, they would have little trouble finding passage to Italy. And we set out to sea – accompanied by Aristarchus, a Macedonian from Thessalonica (27:2b). Aristarchus was with Paul in Ephesus (19:29), accompanied him with the collection from the Gentile congregations to Yerushalayim (20:4), and went with Paul all the way to Rome (Colossians 4:10). It was likely that Aristarchus paid his way as a passenger, and Luke was on board as the ship’s doctor.

The next day we put out to sea, making port the next at Sidon, seventy nautical miles to the north. That would have only taken one day for the ship and her crew. It may have related to commercial factors, the port city of Sidon being a major grain importer. In just one day at sea, Paul won the friendship of the centurion Julius. He treating Paul kindly, let him leave the ship and go to his believing friends at Sidon to receive care (27:3). The kindness Paul received reflected both his status as an uncondemned man awaiting an appeal before Caesar, and his evident godly character, giving him favor before others. In addition, Julius seems like he was naturally kind by nature, and, no doubt, Paul had already made a favorable impression on him. Beside the crew, all the others on board were condemned prisoners (28:42) being sent to Rome to die in the arena.609

From Sidon the direct route to Myra was to the west the island of Cyprus. But setting out to sea from there, we were compelled to sail under the shelter of Cyprus, because the winds were against us. In contrast to the trip from Caesarea to Sidon – which was only 70 nautical miles – the voyage from Sidon to Myra, was a stretch of open sea in excess of nautical 400 miles. Having hugged the shelter of Cyprus as long as possible, the ship then forced its way into open waters between Cyprus and Asia Minor, moving along the coast past Cilicia and Pamphylia with the help of night breezes and westerly sea current. Then Luke commented that we came down to Myra, a port city of Lysia (27:4-5). The length of the voyage was probably around 15 days.

They likely docked at Andriace, which was the chief port for ships that supplied the Roman Empire with Egyptian grain, and especially for those ships that traveled between Alexandria, Egypt and Rome. Being part of the Roman Empire, Egypt was her main source of grain. So these private ships received special consideration from the Roman government in view of the importance of that lifeline.610 There the centurion found a second ship from Alexandria sailing for Italy and put us on board (27:6). The fact that Luke specifically mentions that the ship was carrying wheat (27:38), confirms that she was an Egyptian grain carrier on her way to Rome. This was the larger ship that Julius was looking for. Because of its practical and political significance as a commodity in the ancient world, grain is frequently compared in importance to present-day oil.

Since Egyptian ships carrying grain tended to travel in fleets to gain both safety and navigational advantages, the fact that the ship sailed off alone was very dangerous. Rudderless, they were steered with two huge paddles on each side of the stern. Power depended on a single gigantic square sail made of heavy Egyptian linen or animal hides stitched together. They were not designed for sailing against the wind – which was exactly what the sailors faced on their ill-fated voyage.611 However, the promise of lucrative returns offset the hazards to a significant degree. Profits were high in order to offset the expense of building and maintaining ships the size demanded by the government and could carry between 2,500 and 3,500 tons of wheat.612

However, the Alexandrian ship soon found its course for Italy somewhat difficult. The voyage continued, but with lack of progress because it appeared that they were sailing into the wind. Luke relates that with difficulty we made it to Cnidus, 130 nautical miles away. But when we left Cnidus, we left the shelter of the mainland. As the wind did not allow us to go further west across the lower end of the Aegean Sea, it forced us due south towards Crete. Already the voyage was somewhat off course because the normal route from Myra would have taken the ship past Crete, along its northern coast. However, the winds were so great that we were forced to round Cape Salone and hug Crete’s southern coast. That made sailing slow for a number of days. Coasting again with difficulty, we came to a place ironically called Fair Havens, near the city of Lasea (27:7-8). There, weary from fighting the weather, the weary travelers entered the bay. It is an open bay, a poor harbor in bad weather, but it would protect them for a while from the winds they were facing. The trip from Alexandria to Rome normally took 10 to 13 days, but adverse conditions could slow the trip to as much as 45 days.613

The warning of the storm: Since considerable time had passed at Crete waiting for a change in the winds, the voyage was already dangerous because the Fast of Yom-Kippur on October the fifth that year had already passed (27:9a). Shipping became increasingly dangerous after mid-September and was rarely engaged in after mid-October because of the likelihood of storms. Yom-Kipper can occur between September 14 and October 14. So they had already entered into that dangerous season for sailing.

Apparently the sailors and Julius had a meeting to plan their course of action, where Paul, an experienced traveler, was allowed to speak. He kept on warning them, telling them, “Men, I can see that the voyage is about to end in disaster and great loss – not only of the cargo and the ship, but also of our lives” (27:9b-10) In fact, he had been shipwrecked three times and had been adrift overnight on wreckage (Second Corinthians 11:25). But his advice was overruled and the centurion was persuaded more by the owner and the captain of the ship than by what was said by Paul, which they would later regret (27:11).

In You, ADONAI, have I taken refuge. Let me never be ashamed. Deliver me and rescue me in Your justice. Turn Your ear to me and save me. Be to me a sheltering rock where I may always go. Give the command to save me – for You are my rock and my fortress. My God, rescue me out of the hand of the wicked, out of the grasp of an evil ruthless man. For You are my hope, ADONAI my Lord – my trust from my youth. From my birth I have leaned on You. You took me out of my mother’s womb. My praise has always been about You. I am like an ominous sign to many, but You are my strong refuge. My mouth is filled with Your praise and with Your glory all day (Psalm 71:1-8).

A closer look at Paul’s perils, travels and travails in antiquity: One could hardly find a better description of the perils of travel in antiquity than one finds in Second Corinthians 11:23-29. Paul speaks of danger from bandits, from rivers; of being shipwrecked three times, being adrift in the sea for a night and a day; of having sleepless nights, going hungry and thirsty, being cold and even on occasion also naked; of experiencing anxiety, and this doesn’t even include the difficulties Paul faced because of determined opposition to his ministry by both Jews and Gentiles.

From Paul’s list of perils one might come to the conclusion that it was a very dark time to be on the road. However, it can be argued that the several centuries after Messiah’s death were untroubled days for a traveler. He could make his way from the shores of the Euphrates to the border between England and Scotland without crossing a foreign frontier, always within the bounds of Roman authority. A purse full of Roman coins was the only kind of cash he had to carry; they were accepted or could be changed everywhere. He could sail through any waters without fear of pirates, thanks to the Emperor’s patrol squadrons. A planned network of good roads gave him access to all major centers, and the routes were policed well enough for him to ride them with relatively little fear of bandits. He needed only two languages: Greek would take him from Mesopotamia to Yugoslavia, and Latin from Yugoslavia to Britain. Wherever he went, he was under the protective umbrella of a well-organized, efficient legal system. If he was a Roman citizen and got into trouble, he could, as Paul did, insist upon trial in Rome. This is somewhat optimistic, but it is near the truth to explain why so many believers and unbelievers did so much traveling at that time.

In some parts of the Empire travel on land could be undertaken year-around, or almost so, but travel on sea was limited to the sailing season. The prime time was between May twenty-seventh and September fourteenth, but troops and others who had a necessity or were adventurous might sail in March, April, October, or even November. The sea was very changeable from March 10th to Mary 26th and from September 14th to November 11th, but still sailable. The winter storms made the seas extremely dangerous for sailing in December, January, or February.

There were no passenger ships as we know them today. One had to pay an exit tax to leave a country and book passage on a merchant ship, and while the big ones would venture out into the sea, such as the one Paul sailed on from Patara to Tyre (21:1-3), the smaller ones tended to hug the coastline and pull into port each night. On a big vessel, and with prevailing winds, passage from Rome to Corinth took about five days at least, and Alexandria was ten days from Rome. Most travelers on large ships simply booked passage as deck passengers, sleeping out in the open or under a small tent. They would travel with bags that would contain not only clothes, but also cooking utensils, food, bathing items, and sometimes bedding as well. Sometimes a very large vessel might hold up to six hundred passengers or slaves, but this was out of the ordinary.

In general, ships never left on a fixed schedule, but according to the winds and weather, which meant that if one wished to go on such a ship, one needed to stay near the port, where one could hear the ship’s captain signal departure. Also sailors, like many others in the Roman world, were a superstitious lot, and there were certain days (for example August 24th, October 5th, November 8th, religious holidays, and in general at the end of the month when it was thought unwise to sail. Most ship captains or owners would make a sacrifice before sailing, and if the omens were ill, sailing would be delayed. Some of the above explains why it was that on the one hand Paul was so anxious to sail from Caesarea. One had to go while the going was good, and one could never be sure of making a passage by a certain date unless one made allowance for some of the delaying factors mentioned above.614

Leave A Comment