The LORD’s Wrath Against Isra’el

Second Samuel 21: 1-14

The Lord’s war against Isra’el DIG: What caused the famine (Joshua 9:20)? Why did Isra’el make a treaty with the Gibeonites in the first place? Sha’ul decimated the Gibeonites in his zeal, but David spared them due to an oath before the LORD. What does this say about the basic differences between the two men? About the seriousness of oaths? About God’s judgment? What shocks you about the Gibeonites request and David’s acceptance? Why did David spare Mephibosheth, but not Sha’ul’s other sons (First Samuel 20:14-17)? What contrast between the two does this again highlight? What is significant about both oaths and executions being made before the LORD? What link do you see in 21:1 and 9? Why would it please God to see Sha’ul’s descendants executed?

REFLECT: Are there ways in which we may take the Lord’s name in vain without actually swearing an oath? What about claiming to be guided by Him when we are doing something that is clearly unbiblical? Is a promise always important, no matter how long ago it was made or how inconvenient or costly it is now to fulfill it? This section deals with a very difficult passage. A Bible teacher once said, “I am not too bothered by the Scriptures I don’t understand, although I continue to seek light on them. There is quite enough challenge for me in the passages I do understand.” How would these scriptures fit into that category? What can you learn from this episode about the Gibeonites, David and Sha’ul’s descendants? Which of your actions this week do you want to affirm as being before ADONAI?

The last four chapters of Second Samuel serve as an appendix to David’s career. These events occurred earlier in the king’s life but are presented here to show the other kinds of problems David had to face – famine and plague (Chapters 21 and 24) – the men David relied on to fight his battles (Chapter 23), and how the king learned to praise God through his trials (Chapter 22 and Psalm 22).

When Isra’el suffered famine for three years in succession, David presumed that the LORD was saying something to His people through the disaster. He was not mistaken.464

The Cause: During the reign of David, there was a famine for three successive years; so David sought the face of ADONAI. YHVH’s answer was not long in coming. He told David plainly what was wrong: It is on account of Sha’ul and his bloodstained house; it is because he put the Gibeonites to death in violation of the covenant the Israelites had made with the Gibeonites. At that time Isra’el, under Joshua’s leadership, had just destroyed Jericho and Ai and were about to attack the Amorite federation in the Canaanite hill country. The people of Gibeon, who were in the path of Joshua’s destruction, pretended to be faraway aliens and so escaped annihilation. Not only that, they tricked Joshua into making a covenant with them whereby they would serve Isra’el forever in minor ways but would never be attacked. Joshua 9:16 informs us that Isra’el cut (Hebrew: karath) a covenant with Gibeon. An animal was cut, its pieces put opposite one another, and those taking the covenant obligation would walk between the pieces. By this act they were saying, “As this animal is cut into pieces, so may we be cut up if we do not keep this oath.” Now the Gibeonites demanded that this curse be carried out (see the commentary on Genesis, to see link click Eg – I am the LORD, Who Brought You Out of Ur of the Chaldeans to Give You This Land). ADONAI had declared that bloodshed pollutes the land . . . do not defile the Land where you live and where I dwell, for I, ADONAI, dwell among the Israelites (Numbers 35:33). Now the Gibeonites were not a part of Isra’el but were survivors of the Amorites; the Israelites had sworn to spare them, but Sha’ul, in an action not recorded in the Bible, had tried to annihilate them in his zeal for Isra’el and Judah (Second Samuel 21:1-2). As a result, the underlying cause of the famine was a broken covenant.

Sha’ul’s religious life was a puzzle. Attempting to appear very godly, he would make foolish vows that nobody should keep (First Samuel 14:24-35), while at the same time he didn’t obey the clear commandments of ADONAI (First Samuel 13 and 15). He was commanded to slay the Amalekites and didn’t, yet he tried to exterminate the Gibeonites. Another piece of the puzzle is that Jeiel, Sha’ul’s great-grandfather, was the forerunner of the Gibeonites (First Chronicles 8:29-33 and 9:35-39), so Sha’ul slaughtered his own relatives!465

The king was determined to right the wrong done by Sha’ul. The problem was clear, but the solution was nebulous. So he summoned the Gibeonites and asked them, “What shall I do for you? How shall I make atonement so that you will bless the LORD’s inheritance? Or what can I do so that Isra’el is blessed, rather than being cursed because she had violated the Torah under King Sha’ul. The word atonement is being used here because of Isra’el’s unrepeated murder. The execution would be based upon Numbers 35:31: Do not accept a ransom for the life of a murderer, who deserves to die. They are to be put to death. The Gibeonites answered: We have no right to demand silver or gold from Sha’ul or his family. They did not want any ransom for the death of their people. Nor do we have the right to put anyone in Isra’el to death. The Gibeonites had no authority to execute any Jews. The implication, of course, was that David did have such authority. That was a clear hint, but they weren’t specific. So David asked them, “What do you want me to do for you” (Second Samuel 21:3-4)? Once David got more specific, so did they.

The Gibeonites’ desire for vengeance concerned one man, and since he was dead, focused on his descendents. They answered the king, “As for Sha’ul, the man who destroyed us and plotted against us so that we have been decimated and have no place anywhere in Isra’el, let seven (implying full retribution) of his male descendants be given to us to be killed (the Hebrew word, yaqa, implies impalement) and their bodies exposed before the LORD at Gibeah, ironically, Sha’ul’s hometown – YHVH’s chosen one.” Sha’ul’s bloodstained house would then be completely avenged. So the king said: I will give them to you (Second Samuel 21:5-6). David was the antidote to Sha’ul’s sin.

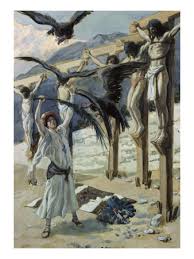

The Solution: The king did not shrink in the heart-rending task of selecting seven grandsons of Sha’ul (perhaps David thought about those who had died because of his sin – Bathsheba’s baby, Uriah the Hittite, Amnon, Absalom and Amasa). However, he spared Mephibosheth son of Y’honatan, the grandson of Sha’ul, because of the oath before ADONAI between David and Y’honatan (First Samuel 20:41-42a). Sha’ul was a covenant-breaker, but David was a covenant-keeper. But the king took Armoni and Mephibosheth, the two sons of Aiah’s daughter Rizpah (Sha’ul’s concubine), whom she had borne to Sha’ul, together with the five sons of Sha’ul’s eldest daughter, Merab, whom she had borne to Adriel son of Barzillai the Meholathite. He handed them over to the Gibeonites, who hanged them and exposed their bodies on a hill before the LORD where they could be easily seen. All seven of them fell together; they were put to death during the first days of the harvest, just as the barley harvest was beginning and the rainy season had ended in the latter part of April (Second Samuel 21:7-9). The Jews would still have to deal with the drought through the end of that year. But after that the rains came, suggesting that God’s curse, which had been on the Land, then rested on the executed sons of Sha’ul for anyone who is hung on a tree is under a curse (Deuteronomy 21:23).466

Most readers are simply appalled at the sheer horror of this scene. That, I think, is the primary application of this passage. We should be aghast. The Bible tells us that atonement is horrible. It is gory. Atonement is never nice, but always gruesome. We need to see the horror of atonement, for we can easily fall into the trap of regarding atonement as merely a sterile doctrine, a concept, an idea to be explained, a bit of theology to be analyzed. Or, little better, to view it as a moving story to be re-played during Passion Week. But we should know better. Surely the Israelite worshiper realized this when he towed a young bull by faith to the Bronze Altar (see the commentary on Exodus Fa – Build an Altar of Acacia Wood Overlaid with Bronze) and had to slit its throat, skin it, cut it into pieces, and wash the insides and legs (Leviticus 1:3-9). It was all mess and gore and flies. Not nice. From slicing the bull’s throat in Leviticus 1 all the way to the old rugged cross, God has always said atonement is nasty and repulsive (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Ls – Then They Brought Jesus to Golgotha, the Place of the Skull). If we’ve grown too accustomed to Golgotha, maybe Gibeah can shock us back to the truth: atonement is a drippy, bloody, smelly business. The stench of death hangs heavy whenever the wrath of God has been quenched.467

The Final Burial of Sha’ul’s Family: Rizpah, mourning her two sons, took sackcloth and spread it out for herself on a rock, making a tent for herself. She could not prevent the executions nor the exposure. There was so much she was helpless to change; but she did what she could. From the beginning of the harvest till the rain poured down from the heavens on the bodies, for seven months, from April to October, she did not let the birds touch her dear ones by day or the wild animals by night (Second Samuel 21:10). When the rains came again, it not only proved that the drought was over and the curse was removed, but even more, it proved the righteousness of the executions. Because their bodies were exposed, she made sure that no birds or wild animals touched them. The Torah states that the bodies had to be taken down by sundown (Deuteronomy 21:22-23). But this was not the case of a simple murder, but also the violation of a sacred covenant. This was a case of expiation of the Land. And if no execution took place, the Land would continue to be polluted (Numbers 35:37). These executions took place to show national responsibility to keep a covenant. The judgment of Sha’ul’s sin was pronounced on him, his household and his descendants. And according to Exodus 34:6-7, in dealing with His covenant nation, God punished to the fourth generation.468

When David was told of Rizpah’s gripping devotion, he was obviously touched by her loving action. So he went and took the bones of Sha’ul and his son Y’honatan from the citizens of Jabesh Gilead. They had stolen their bodies from the public square at Beth Shan, where the Philistines had hung them after they struck Sha’ul down on Gilboa (see Bw – Sha’ul Takes His Own Life). David brought the bones of Sha’ul and his son Y’honatan from there, and the bones of those who had been killed and exposed by the Gibeonites were gathered up. Reinternment of bones was not uncommon in ancient times (for the odyssey of Joseph’s bones see Genesis 50:25-26; Exodus 13:19 and Joshua 24:32), and David intended to give the bones of Sha’ul and Y’honatan an honorable – if secondary – burial. So Sha’ul and his son Y’honatan found their final resting place in the tomb of Sha’ul’s father Kish, at Zela in Benjamin territory. The execution of the seven had atoned for Sha’ul’s sin and fully satisfied (propitiated) the wrath of God over defiling the Land. After that, justice had been done, and ADONAI answered prayer on behalf of the Land (Second Samuel 21:11-14).

The Ruach ha-Kodesh wants to leave you sad and solemn – He doesn’t want you running off to your next activity. There is something incredibly sad about this sight. And often there is goodness in sadness: It is better to go to a house of mourning than to go to a house of feasting, for death is the destiny of everyone; the living should take this to heart. Frustration is better than laughter, because a sad face is good for the heart. The heart of the wise is in the house of mourning, but the heart of fools is in the house of pleasure (Ecclesiastes 7:2-4). Here is a gut-wrenching mystery. And the Writer would fill your senses with it, as if to say, “Look what comes from covenant-breaking.”

Psalm 90:11 comes to mind: Who can comprehend the power of Your anger? Your wrath is as awesome as the fear You deserve. Whoever stops to consider the wrath of God? The Psalm answers, almost no one. However, the Spirit says that you should. Stay at Gibeah. Let it sink into your pores. Share the tragedy. It will do you good. Remain at Golgotha. Let the sadness sink in. Consider the wrath of YHVH and ponder the paths of love: This is love: not that we loved God, but that He loved us and sent His Son as an atoning sacrifice for our sins (First John 4:10).469

Leave A Comment