Jeremiah Thrown into a Cistern

38:1-28 and 39:15-18

Jeremiah thrown into a cistern DIG: What does this “gang of four have against Jeremiah? Why does the prophet react to them the way he does? Why don’t they just kill Yirmeyahu and get it over with? In using a cistern to do the job, what might the king be secretly hoping? Who stands up for the prophet and why? Why the details about the thirty men and the old rags? Is Jeremiah reluctant to answer Zedekiah, or is he simply negotiating (compare Yeshua’s same predicament in Luke 22:66-67)? Why didn’t Zedekiah either kill God’s prophet or listen to his counsel? What does he stand to lose either way? Why is the king afraid to surrender (verse 19)? Who else is he afraid of (verses 24-26 and 16)? What one word describes Zedekiah? Who were those women? Is the omission of true and relevant facts the same as lying? Do you always try to tell the truth, or is there a time for discretion, or silence as in Yirmeyahu’s case?

REFLECT: What has been your spiritual low point? Where did you receive help? Were any “old rags” or trusted friends used in your rescue? Like king Zedekiah, do you come off as “everybody’s friend?” Explain? When was the last time you were in a no-win situation? How did you handle it? Who do you know that shows interest in Christ time after time, but never really takes the step of faith? What fears lie behind the mixed feelings? Are there any areas of your life that you have not given totally to Yeshua? Why? What needs to happen to change that? Who can you talk to about it?

587 BC at the end of the eleven-year reign of Zedekiah

It was a late, ominous time for Jerusalem and for its king . . . Zedekiah. Once more, this narrative concerns a confrontation between the king and the prophet. They are the two principle actors in the story, and they embody two contrasting perspectives. The king is fragile and desperate. His only concern in this account is the development of a policy of survival for Zion. His counterpart, the prophet, is by now persona non grata among the leaders of Yerushalayim, for he was not supportive of their fanciful policies. While Jeremiah’s position had important implications for the survival of Judea that was not his major concern. He was obsessed with the will and purpose of YHVH as the foundation of public life of Y’hudah. The conclusions the prophet draws from his discernment about the will and purpose of ADONAI are not conducive to the survival of Zion as seen by the king.346

Jeremiah was thrown into a cistern: We are very close to the end of the long rule of the Davidic line. No wonder there is tension, hostility, distrust and panic among the leaders. Shephatiah son of Mattan, Gedaliah son of Pash’chur, Jehukal son of Shelemiah, and Pash’chur son of Malkijah heard what Jeremiah was telling all the people. Apparently, Jeremiah’s transfer to the courtyard of the guard (37:21) provided him an opportunity to address the people. At that time the prophet declared: This is what ADONAI says: Whoever stays in this city will die by the sword, famine or plague, but whoever goes over to the Babylonians will live. They will escape with their lives . . . they will live. And this is what the LORD says: This city will certainly be given into the hands of the army of the king of Babylon, who will capture it (38:1-3). The reason Shephatiah, Gedaliah, Jehukal, Pash’chur and the other officials of Judah wanted to kill Yirmeyahu was because of the prophet’s insistence that they surrender to the Babylonians.

The officials of Y’hudah had such power that, humanly speaking, if Jeremiah allowed his mind to wander from his calling he might have been intimidated by them. It is probably more correct to say that Zedekiah allowed them to have this power. The prophet was correct in his assessment when he asked the king not to send him back to the house of Jonathan or he would die there (37:20). Then the officials said to the king, “This man should be put to death for two reasons. First, he is discouraging the soldiers who are left in this city, as well as all the people, by the things he is saying to them. And second, treason, this man is not seeking the good of these people but their ruin.” He is in your hands, king Zedekiah answered: The king can do nothing to oppose you (38:4-5). What a coward.

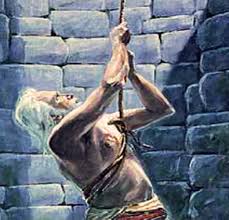

Perhaps the officials were afraid to murder the prophet outright and shrank from superstitious dread from such an act; but they conspired on a plan that would accomplish the same result. So they took Yirmeyahu and put him into the cistern of Malkijah, the king’s son, which was in the courtyard of the guard. The cisterns of the time were typically shaped like a huge bottle, with a large diameter but only a small opening at the top, which was often covered with a stone. They lowered Jeremiah by ropes into the cistern. It seemingly had contained water earlier, but it had been depleted during the siege and at this point it had no water left in it, only mud, and Yirmeyahu sank down into the mud (38:6). Yirmeyahu was fully aware that he wouldn’t last very long in it.

This was the third time Jeremiah was imprisoned. First, Pash’chur had him beaten, put in stocks and then put in prison (to see link click Da – Jeremiah and Pash’chur). Secondly, after Yirmeyahu was falsely accused of desertion, he was beaten and imprisoned in the house of Jonathan the secretary, which they had made into a temporary prison (see Fm – Jeremiah in Prison). And thirdly, here, where he was put into the cistern of Malkijah, the king’s son, which was in the courtyard of the guard, and left to die.

But once again God fulfilled His promise to Jeremiah that he would not die at the hands of men (1:19). The LORD used Ebed-Melek, a God-fearing Cushite from Ethiopia, and an official (Hebrew: saris, meaning eunuch) in the royal palace as His servant. The name Ebed-Melek is made up of two Hebrew words meaning the servant of the king. He was an Ethiopian and not a Jew. As a eunuch, the Torah excluded him from the congregation of Isra’el (Deuteronomy 23:1). But when he heard that they had put Jeremiah into the cistern, the Cushite knew the prophet would die from either suffocation or exposure if not rescued quickly. Being lead by YHVH, Ebed-Melek immediately went to the king and confronted him with the injustice that he had permitted.

While the king was sitting in the Benjamin Gate (because of the heavy traffic through this gate, it became a convenient place for the administration of justice), Ebed-Melek went out of the palace and sought him out, saying to him, “My lord king, these men have acted wickedly in all they have done trying to kill this man. They have thrown him into a cistern, where he will starve to death when there is no longer any bread in the city” (38:7-9), a natural exaggeration in the effort to plea for Jeremiah’s release. The thought being that the shortage was so severe that no one would think about feeding Yirmeyahu who would be hidden away out of sight.

As astonishing as the eunuch’s boldness, was the king’s lack of anger. Then the king commanded Ebed-Melek the Cushite, “Take thirty men from here with you and lift Jeremiah the prophet out of the cistern before he dies.” Why thirty men? Thirty was too many to merely lift Yirmeyahu out of the cistern, but it was enough to stop any interference from the four bloodthirsty officials. So Ebed-Melek took the men with him and went to a room under the treasury in the palace. He took some of the old rags and worn-out clothes from there and let them down with ropes to Jeremiah in the cistern. The eunuch didn’t want any ropes to cut into the prophet. He was really looking out for God’s messenger. Ebed-Melek the Cushite said to Yirmeyahu, “Put these old rags and worn-out clothes under your arms to pad the ropes.” Jeremiah did so and they pulled him up with the ropes and lifted him out of the cistern. That Gentile gave Yirmeyahu much more respect than the Jews did. And Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard (38:10-13).

Yirmeyahu was never popular. He was never surrounded with applause. However, he was not friendless. In fact, Jeremiah was extremely fortunate in his friendships. Twenty-one years earlier the prophet was almost murdered, but Ahikam ben Shaphan intervened and saved his life (see Cg – Jeremiah Threatened With Death). Baruch was his disciple and scribe, loyal and faithful, sticking with him through difficult times to the very end in Egypt. And Ebed-Melek the Ethiopian eunuch, came to his aide. “One friend in a lifetime is much,” wrote Henry Adams (American historian and member of the Adams political family 1838-1918), “two are many; three are hardly possible.” Jeremiah had three.

While Yirmeyahu had been put into Malkijah’s cistern in the courtyard of the guard (38:6), the word of ADONAI came to him saying: Go and tell Ebed-Melek the Ethiopian, “This is what ADONAI-Tzva’ot, the God of Isra’el, says: I am about to fulfill My words against this City – words concerning disaster, not prosperity. At that time they will be fulfilled before your eyes.” But I promise that I will rescue you on that day; you will not be given into the hands of those [court officials] you fear. I will save you; you will not fall by the sword but will escape with your life, because you trust in Me” (39:15-18). God promised to do for Ebed-Melek exactly what He would not do for Zedekiah. The contrast was sharp. The Ethiopian trusted in God while Zedekiah did not.

Ebed-Melek risked his life when he confronted Zedekiah about Jeremiah. Being a foreigner he had no legal rights. He was going against popular opinion in a crisis that was hysterical with wartime emotion. That didn’t matter. A friend is a friend. The Cushite didn’t indulge in sentimental pity for Yirmeyahu, philosophically lamenting his fate; he went to the king, he got ropes, he even thought of getting rags for padding so that the ropes wouldn’t cut, he enlisted help, and he pulled the prophet to safety. He acted on his friendship.

The simple fact that Jeremiah had friends says a lot about the prophet. He needed friends. He was well developed in his internal, private life. It was impossible to deter him from his course by hostility or by flattery. He was used to the solitude. But he needed friends. No one who is whole is self-sufficient. The whole life, the complete life, cannot be lived by arrogant independence. A person without friends is a person in trouble. Our goal cannot be to not need anyone. One of the evidences of Jeremiah’s wholeness was his ability to receive friendship, to let others help him, to be open to mercy. It is easier to extend friendship to others than to receive it ourselves. In giving friendship we show strength, but in receiving it we show weakness. But well-developed people are never fortified behind doctrines or projects, but rather they are active in a wide range of relationships.347

Zedekiah questions Jeremiah for the third time: Then King Zedekiah sent for Jeremiah the prophet a third time and had him brought to the [private] entrance to the Temple of ADONAI. Then surprisingly, the king opens his heart to the priest from Anathoth. “I am going to ask you something, the king said to the prophet, “Do not hide anything from me.” Yirmeyahu said to Zedekiah, “If I give you an answer, will you not kill me? Even if I did give you counsel, you would not listen to me.” But King Zedekiah swore this oath secretly to Jeremiah, “As surely as ADONAI lives, who has given us breath, I will neither kill you nor hand you over to those who want to kill you” (38:14-16). But if you notice, he did not promise to follow Jeremiah’s counsel.

This led God’s messenger to move from his former courtesy to great frankness. Then Jeremiah explained as before: This is what ADONAI-Tzva’ot, the God of Isra’el, says: If you surrender to the officers of the king of Babylon, your life will be spared and this city will not be burned down; you and your family will live. But if you will not surrender to the officers of the king of Babylon, this city will be given into the hands of the Babylonians and they will burn it down; you yourself will not escape from them (38:17-18). The two options Jeremiah provided for the people, he now provides for their king. Nothing had changed.

Then the king unburdens himself, confessing his fear of those in the City who have already deserted to the enemy: I am afraid of the Jews who have gone over to the Babylonians, for the Babylonians may hand me over to them and they will mistreat me (38:19). Many Jews had gone over to the Babylonians (39:9, 52:15, 21:9, 38:2) from Jeremiah’s own advice. He was afraid they would mistreat him. The word mistreat means to abuse by mockery or physical abuse. One usually comes with the other (see the commentary on The Life of Christ Lu – Jesus’ First Three Hours on the Cross: The Wrath of Man).

The final warning to the last king of Judah: Jeremiah reassures the king that his fear is an empty one. They will not hand you over, Yirmeyahu replied: Obey the LORD by doing what I tell you. Then it will go well with you, and your life will be spared. But if you refuse to surrender, this is what ADONAI has revealed to me (38:20-21). The relationship between the two is strange: on the one hand, the king, who presumably has all the power and whom Yirmeyahu has treated respectfully but who cannot face down his own officials in their opposition to the prophet. On the other hand, YHVH’s messenger, whom the king seems utterly dependent for advice, is being variously restricted.

Then the prophet goes on to share with him a vision he has had of the women of the palace taunting their king as they are led out to captivity. Zedekiah would be both mocked and abused physically: All the women left in the palace of the king of Judah will be brought out to the officials of the king of Babylon. Zedekiah would be mocked. But not by those he feared (38:22a), but by the women of his own royal harem! Sometimes a defeated king would merely be made a vassal without the humiliation of having another king take over his harem. But having another king take over your harem was the ultimate mockery for a king (Second Samuel 16:20-22). Those women will sing a taunt (mocking) song:

The first line is a paraphrase from Obadiah 7: Your own close friends misled you and took advantage of you. The second line is a flashback to Jeremiah’s own recent experience in the cistern of 38:6, in which he sank down into the mud. Now it would be Zedekiah who would sink down into the mud, but he wouldn’t have Ebed-Melech to lift him out like Yirmeyahu did. Now that your feet are stuck in the mud, they have abandoned you (38:22b). Therefore, Zedekiah’s fear of mocking would come true if he disobeyed Jeremiah’s counsel, and it would come both from women (38:22) and men (39:6-7).

All your wives and children will be brought out to the Babylonians. You yourself will not escape from their hands but will be captured by the king of Babylon; and this city will be burned down (38:23). By following a policy against which Jeremiah had persistently but unsuccessfully warned him, Zedekiah was responsible for the City being destroyed by fire.

Then Zedekiah said to Jeremiah, “Do not let anyone know about this conversation, or you may die (38:24). If the officials hear that I talked with you (and they probably would, since what happens in a court can rarely be kept secret), and they come to you and say, ‘Tell us what you said to the king and what the king said to you; do not hide it from us or we will kill you,’ then tell them, ‘I was pleading with the king not to send me back to Jonathan’s house to die there’ (38:25-26).” Jeremiah was not to tell the full truth, but then again, he would not be lying. But he obviously didn’t tell them the whole truth. Jeremiah could not communicate with these officials even if he had wanted to, without betraying a confidence.

And just what Zedekiah feared did come true. All the officials did come to Jeremiah and question him, and he told them everything the king had ordered him to say. So they said no more to him, for no one had heard his conversation with the king (38:27).

And Jeremiah remained in the courtyard of the guard until the day Jerusalem was captured (38:28). He remained until the bitter end. One sees in this steadfast resolve to stay with the struggle to suffer along with everyone else to the bitter end, a modern parallel in the commitment of Dietrich Bonhoeffer, German theologian and martyr of the Nazi era, who in 1939 made the courageous decision to leave New York, where he had gone for a brief sojourn and where he had been offered safe haven, and return to Germany, where he felt the obligation to join in the struggle with his own people until the war ended. His last act before being hanged by the Gestapo was to celebrate communion with his fellow prisoners.348

Leave A Comment