Letters to Ahasuerus and Artakh’shasta

Ezra 4: 6-16

Letters to Ahasuerus and Artakh’shasta DIG: Artakh’shasta reigned from 486 to 465 BC. How does the opposition under their reigns compare to the opposition under King Cyrus (4:1-6). How do you account for the perseverance and intensification of this conflict over such a span of years? Ashurbanipal squelched a major revolt in Babylonia (652-648? BC), destroyed the town of Susa in the process, and deported the rebels (4:10). What irony do you see in what Rehum (and the other descendants of those rebels) are doing two centuries later? What was their letter designed to do (4:11-16). How is that related to what transpired one century earlier (under the reign of King Cyrus)?

REFLECT: Rehum’s complaints against Isra’el remind us that our past sometimes lives on to haunt us. Where do you see that today in national or international affairs? In churches? In messianic synagogues? In denominations? In your personal and family life?

445 BC During the ministry of Nehemiah (see Bt – The Third Return).

Compiled by the Chronicler from the Ezra and Nehemiah memoirs.

(see Ac – Ezra-Nehemiah from a Jewish Perspective: The Nehemiah Memoirs).

In describing the events in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah, the Chronicler, with the advantage of hindsight, looks back on the historical landscape and refers to the opposition placed in the way of the Jews. When discussing the problems of building the Temple in Ezra 4:1-5, it reminded him of similar problems with the rebuilding of the walls of Jerusalem about ninety years later, and so Ezra 4:6-23 has been inserted, almost parenthetically, before the narrative of the building of the Temple can once again be taken up in Ezra 4:24. So, here we temporarily flash-forward to 445 BC and the Third Return of Nehemiah.

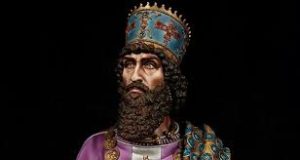

Opposition during the reign of Ahasuerus: During the reign of Ahasuerus at the beginning of his reign (see the commentary on Esther Ac – The Book of Esther From a Jewish Perspective: King Ahasuerus), they wrote an accusation against the inhabitants of Judah and Jerusalem (Ezra 4:6). The beginning of his reign is an Aramaic technical term translated into Hebrew. It refers to the time of the actual assumption of power and not the year in which the king ascended to the throne. The latter year is usually counted as the last year of the previous king. The beginning of the reign of Ahasuerus, therefore, refers to 485 BC. It seems that the complaint had not been heeded because Ahasuerus had put down a revolt in Egypt.70 Troubling a new ruler eager to assume a formidable reputation was, of course, a good strategy on the part of Jerusalem’s enemies. The attempt seems to have come to nothing, however, and the story moves on.

Opposition during the reign of Artakh’shasta: More than twenty years later, following the assassination of Ahasuerus by Artabanus, the commander of the royal bodyguard, his brother Artakh’shasta ascended to the throne in 465 BC. A letter to the new Persian king accused the Jews of tax avoidance (among other things). The letter itself comes across as a mixture of flattery, innuendo, and political ingenuity.

It is estimated that the Persians collected between $145 and $255 million worth of taxes, of which around $5 million came from Judah. The Persians took gold and silver coins, melted them down, and stored them as bullion. Very little of these taxes returned to the provinces, either by way of expenditure of infrastructure or in social benefit. Though the total amount of income from the Jewish province amounted to less than 5 percent of the total revenue, the Persians would not have tolerated any signs of rebellion on the part of Judah. The threat of the loss of revenue (Ezra 4:13), and, more importantly, political control – you will no longer have any possession in Trans-Euphrates (Ezra 4:16) – no doubt was designed to strike a chord deep within the distant king’s heart.73

Also during the days of Artakh’shasta king of Persia, a letter was written by Bishlam, Mithredath, Tabeel and the rest of his associates to the king of Persia. The letter was written in Aramaic and translated (Ezra 4:7). Aramaic was the official language of diplomacy between the local provinces and the Persian court. The true colors of the adversaries of the Jews appear in this letter. Here their tactics had changed. Now the adversaries (although a new generation of them) were addressing the seat of the empire rather than to the exiles themselves. Their concern, from stressing their similarities, was to show how different they were. They did this by presenting themselves as good and loyal imperial subjects.74

Ezra 4:8 to 6:18 is written in Aramaic, the language the Persians used in official documents (much like the Roman Empire used Greek). This shift gives us the feel that the actual sources are being quoted.

Verses 8 to 11 serve as the introduction to the letter quoted in verses 12 to 16. Rehum the commander and Shimshai the scribe wrote a letter concerning Jerusalem to King Artakh’shasta as follows (Ezra 4:8). Here the author explained that this was a letter of accusation from the officials in Samaria against the Jews who were attempting to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem.

The letter was from Rehum the commander, Shimshai the scribe, and the rest of their associates – the judges and the officials, the magistrates, and governors over the Erechtites, the Babylonians, the people of Susa (that is, the Elamites) and the rest of the peoples whom the great and noble Ashurbanipal deported and settled in the city of Samaria and the rest of Trans-Euphrates (Ezra 4:9-10). Rehum and Shimshai were probably Persian officials who were bribed to write the letter for the Jews in Palestine. In their introduction they tried to point out to Artakh’shasta that the people who opposed the building of the walls of Yerushalayim were from various parts of the Persian Empire. (Now this is a copy of the letter they sent to him). To Artakh’shasta the king, from your servants, the men of Trans-Euphrates (Ezra 4:11).

Sometime before Nehemiah had succeeded with his request (see Bw – The Response of King Artakh’shasta), the Jews started building the wall and the ruins of Jerusalem. Rehum and his associates thwarted that effort. Now let it be known to the king that the Jews who came up to us from you have gone to Jerusalem and are rebuilding the rebellious and wicked city. They are completing the walls and repairing the foundations (Ezra 4:12). This refers to the Jews who migrated to Palestine before Nehemiah (see Bt – The Third Return). They arrived in the City without walls and consequently they were easy prey for robbers. It was understandable that they decided to rebuild the wall to protect themselves and their property. But they had not received permission from the Persian government.75

Furthermore, let it be known to the king, that if this city is rebuilt and its walls are completed, no more tribute, taxes or duty will be paid and the royal revenue will suffer (Ezra 4:13). After the costly campaign against the Greeks, the Persian Empire could not afford to lose any revenue and the conspirators played upon the fears of the king. The early years of Artakh’shasta’s reign had been difficult, and there were a number of rebellions in the west; so even though those supposed dangers were exaggerated in this letter, they would arouse concern in the king, causing him to take notice and act.

Now since we eat the salt of the palace, and it is not proper for us to see the king dishonored, we are sending this message to inform the king so that a search may be made in the book of records of your fathers and you will discover in the records and know that this city is a rebellious city, harmful to kings and provinces, inciting internal revolts from ancient times (Ezra 4:14-15a). Salt was often used to seal covenants; thus it implies loyalty (Leviticus 18:19; Second Chronicles 13:5). So eating the salt of became an idiomatic expression for being “in the service of.” A pretense of loyalty and concern for the king’s honor on the part of Rehum and Shimshai is used with no mention of his true motive of personal gain.

That is why this city was destroyed (Ezra 4:15b). The Persian kings considered themselves the successors of the Babylonian kings, who are referred to here as your fathers. The officials knew that records were kept from former administrations. In fact, kings in the ancient world kept records known as the royal chronicles (see the commentary on Esther Be – That Night the King Could Not Sleep). There is some irony in the statement: That is why this city was destroyed. While that was the Babylonian motivation, the real reason was the judgment of God (Second Chronicles 36:15-19). The Chronicler was certainly aware that the plans of ADONAI supersede human intentions (Ezra 1:1 and 5:12).76

The made-up nature of the accusations in the letter are revealed not only by the use of such incendiary terms as rebellious (verses 12 and 15), wicked (verse 12), harmful (verse 15), and revolts (verse 15, or by pandering to the fiscal concerns of the crown (verse 13), but also to the exaggerated and impossible claim of the effects such a rebellion by Jerusalem would have: We are informing the king that if this city is rebuilt and its walls completed, you will no longer have any possession in Trans-Euphrates (Ezra 4:16).77 Their opposition was obviously not against rebuilding the Temple, for it had been completed in 515 BC (see Af – Ezra-Nehemiah Chronology). The opposition was against an attempt to begin rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem. The letter added that if Tziyon was fortified then the Jews would be able to take back all the territory they had previously occupied, then Artakh’shasta would have no more territory (and taxes) left there.

Although the Jews had often been rebellious under the Assyrian and Babylonian kings, certainly this little band of Jews could not pose a serious threat to Artakh’shasta. However, because of prior troubles in the west (Syria-Palestine-Egypt), Artakh’shasta would have been sensitive to any signs of unrest. But, in reality, this was an exaggerated and impossible claim. Nevertheless, as we shall see next, the king’s prompt, thorough, and positive response attested to the effectiveness of Rehum’s letter.

The work of ADONAI in all ages has known the pressures and persecutions of those who would seek to frustrate its advance. The gross distortions of the charges brought against the Jews in this passage and the apparent unnecessary display of force at its conclusion are no more stranger to the Church than to Isra’el. Indeed, the misinterpretation of a spiritual stance as being political was never more clearly seen than in the trial of Yeshua Himself. He, therefore, must provide the pattern for our response as believers; a relentless hatred for sin and a willingness to fight it where it shows itself, coupled at the same time with an unqualified love for the sinners who may be in the grip of forces quite beyond their understanding. These two can only be held together when we recognize that the weapons of our warfare are spiritual (Ephesians 6:10-17), and that the victory of the cross was won by love and sacrifice rather than by confrontation. Thus, when we face opposition, we dare not ignore these verses to the threat that so persistently confronts us.78

Leave A Comment