Nehemiah Inspects Jerusalem’s Walls

Nehemiah 2: 11-20

Nehemiah inspects Jerusalem’s walls DIG: What do you think Nehemiah did his first three days in Jerusalem? Why was that important? Why do you think Nehemiah said nothing to those who would be doing the work until he had inspected the walls himself? Why inspect the walls at night? What three points does Nehemiah make publicly to rally the troops to rebuild? Which one do you find most convincing? How does Nehemiah respond to his opponents’ changes?

REFLECT: When is it hardest for you to act: (a) When your project lies in ruins? (b) When your workers are few? (c) When others mock you? (d) When you must “buck City Hall” to get a permit? How do you know if God is with you in some enterprise? Where are you looking for God’s “Yes” to help you overcome others “No?”

445 BC During the ministry of Nehemiah (to see link click Bt – The Third Return).

Compiled by: The Chronicler from the Ezra and Nehemiah memoirs

(see Ac – Ezra-Nehemiah from a Jewish Perspective: The Nehemiah Memoirs).

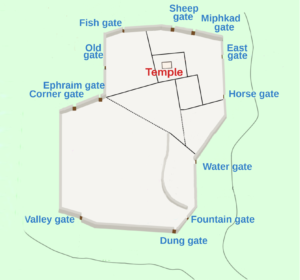

Nehemiah proved to be a hard worker. But hard work alone does not insure success. You need to work hard and work smart. That takes planning. Praying and trusting in ADONAI does not mean that research is not necessary. Nehemiah wanted to assess the situation before presenting his project to the officials and the people. Specifically, Nehemiah needed to know where to rebuild the old walls and where to construct new ones (to see a 3D model of Jerusalem’s gates and walls click here).

Nehemiah came to Jerusalem (Nehemiah 2:11a). At this point, Nehemiah acts quite differently from what we might expect. The hurried reader would think that Nehemiah, having reached his destination, would be driven to pull out his tools, hire subcontractors, hang the plumb line and get to work. But he didn’t do that. As a matter of fact, he didn’t do anything for three days (Nehemiah 2:11b). Why didn’t he go to work? Because he didn’t know what God had for him. As a matter of fact, God was silent.

But shortly thereafter, notice what happened next: I got up during the night along with a few men. But I did not tell anyone what my God had put in my heart to do for Jerusalem. There were no animals with me except the animal I was riding (Nehemiah 2:11c-12). He only used one mule so as not to draw attention to himself. Unlike what happened to Ezra (Ezra 4:12), he didn’t want opposition before he got started. He gained this information in secret because he knew that his enemies were watching him, and he didn’t know who could be trusted. He probably suspected that even some of the Jews in the City were loyal to Sanballat and Tobiah, so to be safe he didn’t even tell the Jews, the cohanim, the nobles, the officials or the rest of the workers (Nehemiah 2:16b).220

In the sixth example of leadership in the life of Nehemiah, competent leaders know how to handle themselves in solitude (to see link click Bt – The Third Return). This is the side of leadership that the uninvolved observer, or even the workers, never see. People have the false idea that a leader lives an exciting life in the limelight, basking in the experience of one ecstatic round of public applause after another. But ADONAI shows us here that successful leaders know how to handle themselves in solitude. In fact, effective leadership is like an iceberg . . . ninety percent is below the surface and unseen, while only ten percent is above the water line, visible for all to see.

By night I went out by the Valley Gate (see Nehemiah’s night ride below), identified as the chief gate in the west wall of the City overlooking the Tyropoeon Valley, toward the now unknown Jackal Spring and the Dung Gate (see the commentary on Jeremiah Cz – Judah is Like a Broken Jar), through which the Cities refuse was carried and deposited outside the wall, inspecting the walls of Jerusalem, which had been broken down (Hebrew: perotzim), and its gates, which had been destroyed by fire (Nehemiah 2:13).

Then I moved on to the Fountain Gate, receiving its name on account of its nearness to the En-rogel fountain, below the junction of the Kidron and Hinnom Valleys, north-east of the Dung Gate and to the King’s Pool, or a receiving pool for the overflow of the Pool of Siloam and located outside the City wall, where there was not enough room for my animal to pass with me because of the rubble and fallen stones from the destruction of the City (see the commentary on Jeremiah Ga – The Fall of Jerusalem), the walls obstructed my passage. So, I had to dismount and proceed on foot; so I went up the valley by night, examining the wall. Finally, I turned back and returned to the Valley Gate rather than along the wall because of all the debris. Apparently Nehemiah did not make the complete circuit of Tziyon but retraced his steps and entered the City where he had gone out. The officials did not know where I had gone or what I was doing (Nehemiah 2:14-16a). Nehemiah’s leadership is evident here. He knew when to keep quiet and when to present God’s project.

Nehemiah was a leader who knew how to inspire action, and he invited all of the Righteous of the TaNaKh to join with him in the work. It was not Nehemiah’s project but ADONAI’s, and He had called all His children to be involved in His work. This would also enable Nehemiah to discover who was fully committed to the plans of God, as those would be the people who threw themselves into the rebuilding.

While Nehemiah identified with the people and was personally concerned with the problem, he did not hide the hard facts. Then, on the following day, I said to them, “You see the bad situation we are in: Jerusalem is desolate and its gates have been burned. Come! Let us rebuild the wall of Jerusalem so that we will no longer be a disgrace” (Nehemiah 2:17). This was Nehemiah’s motivation in undertaking that huge project: he was concerned about the glory of God. The destruction of the Temple and the city of Jerusalem had made a mockery of God’s name in the eyes of Judah’s enemies, so Nehemiah called on the righteous of the TaNaKh to restore His glory to the world around them.221

Then I told them how the good hand of my God was on me (see Ezra 7:9, 28, 8:22 and 31; and Nehemiah 2:8) and the words that the king had said to me. Then they replied, “Let us begin building!” Nehemiah came to the people with compassion, realism, conviction, and faith; thus, ADONAI used Him to communicate his own vision and motivate the people. So, they prepared themselves for this good work (Nehemiah 2:18).

But when Sanballat the Horonite, Tobiah the Ammonite official and Geshem, a powerful chieftain of Kedar in Arabia who was an ally with the Samaritans against the Jews, heard about it, they mocked and ridiculed us. Those three, then, represented the rulers of provinces to the northeast (Ammon), northwest (Samaria), and southeast (Edom and Mo’ab) of Jerusalem. These enemies, especially Sanballat and Tobiah, knew that Nehemiah had credentials from the king (see Bw – The Response of King Artakh’shasta). Therefore, they tried to stop the work by disheartening the people who were doing the building. They used mockery and ridicule as their tool. They even accused the Jews of rebellion. They said: What is this you are doing? Are you rebelling against the king (Nehemiah 2:19)?

When the enemies of God’s work cannot find any legitimate basis for opposition, they may use ridicule, questioning the significance of our labors. This sometimes does more harm than even questioning one’s credentials or good intentions (which Nehemiah’s enemies also did) because it attacks the very motivation for action. Ridicule is especially hard to endure when you are outnumbered. Believers experiencing ridicule should remember what Hebrews 11:36-39 says about the biblical heroes of our faith: Some faced jeers and flogging . . . the world was not worthy of them . . . these were all commended for their faith. Yeshua also suffered ridicule and mocking on many occasions (see The Life of Christ Lu – Jesus’ First Three Hours on the Cross: The Wrath of Man), and His children can expect to face the same kind of opposition.222

And you know something? Nehemiah’s adversaries didn’t leave. They criticized, ridiculed, and dogged his steps through the entire project, until the last stone was set in place. When it was halfway finished, they said mockingly: Even if a fox climbed on what they are building, it would break down their stone wall (Nehemiah 4:3)! This was just a foretaste of the opposition to come.

I responded to them saying: The God of heaven will bring us success. We His servants will arise and build. But you have no part, right, or historical claim in Jerusalem (Nehemiah 2:20). Apparently, these opponents thought they were following the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob if we can judge by the names of their children, and were demanding participation in the rebuilding (Ezra 4:3). Yet, mixing the worshiping YHVH with other gods just ends up being paganism. Nehemiah wouldn’t accept their brand of syncretism, but declared that God would only bless those who served Him alone. Some of the Jewish families, however, did form relationships with the pagans. Later, one of Sanballat’s daughters was married to a member of the Jewish high priest’s family (Nehemiah 13:28).

However powerful the drive might be to labor in the service of our Lord, Nehemiah adds another, arguably even more powerful motivation: the promise of divine approval and divine help in the task before us. The plan to rebuild the walls was not merely Nehemiah’s or the people’s; it was ADONAI who put it into Nehemiah’s heart (Nehemiah 2:12). He reassured the people that this was indeed the case, saying: I told them how the good hand of my God was on me (Nehemiah 2:18). Nothing could have signaled YHVH’s hand more clearly than the fact that King Artakh’shasta had himself given written, documented support for the project! Of this they could be certain; Ha’Shem was behind this work, no matter how difficult it might be and no matter what threats might exist against them if they were to undertake it.

The sufficiency of YHVH is a powerful motivator. Nehemiah was a leader whose vision was filled with the greatness of God. No task is too difficult when the Creator of heaven and earth is the One orchestrating it and in whose hand you are but a tool. A God who can turn the sea into dry land, and can cause a bush to burn without it being consumed, is not going to balk at a Sanballat, a Tobiah, a Geshem, or whoever is opposing you! No sooner had they begun their work, as we have seen, than opposition reared its ugly head. But Nehemiah’s response was this: The God of heaven will bring us success. We His servants will arise and build (Nehemiah 2:20).

Nehemiah’s attitude is captured vividly in Psalm 87: He has founded His City on the holy mountain of Tziyon. ADONAI loves the gates of Tziyon more than all the other dwellings of Jacob. Glorious things are said of you; City of God; I will record Rahab and Babylon among those who acknowledge Me – Philistia too, and Tyre, along with Cush – and will say, “This One was born in Tziyon.” If there is one particular lesson that this section of Nehemiah is meant to teach us, it is that we should trust YHVH more than we do. In matters in which His will is made clear to us, we are not to believe the forces of opposition that come against us, no matter how great they may be; rather, we are to put our confidence resolutely in the Lord. If we trust God, we have nothing to fear.223

A plan is primary; waiting for God to work is essential; but following through with people is where it’s at. In the next file we will move into the phase where the rubber of leadership meets the road of reality – the whole issue of stimulating and motivating others to roll up their sleeves and get the job done.224

Leave A Comment