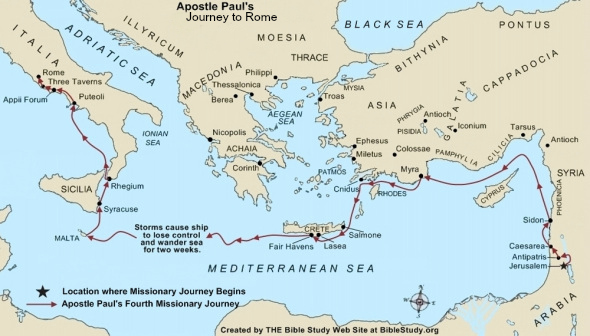

Dg – Paul’s Fourth Missionary Journey

Paul’s Fourth Missionary Journey

62-66 AD

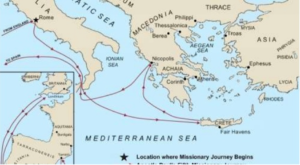

Paul returned to the provinces of Macedonia, Achaia, and Asia and then turned west to Spain according to his original plans (Romans 15:22-28). Then he most likely ministered once more in the Aegean area where he was once again taken prisoner and taken back to Rome one last time to be executed by Nero.657

Fourth Missionary Journey: Pastoral Letters

62 AD After Paul was acquitted and released, he probably went to Macedonia and wrote First Timothy (about the Church), this can be seen from Philippians 2:24 and First Timothy 1:3). Then he went on to Colosse (Philemon 22).

63 AD He may have gone to Spain (Romans 15:24 and 28).

64 AD Paul might have gone to Ephesus (First Timothy 1:3), then went over to Crete (Titus 1:5) and Corinth (Second Timothy 4:20) in Macedonia (First Timothy 1:3) where he wrote Titus (about the Church) before finally coming back to Ephesus once again (First Timothy 3:14).

65 AD After that, Paul probably traveled to Miletus (Second Timothy 4:20), and then he may have traveled to Troas (Second Timothy 4:13), finally coming to Nicopolis (Titus 3:12).

66 AD Paul was once again taken prisoner and taken back to Rome. During his trail he realized that it was going badly and wrote Second Timothy during his imprisonment.

67 AD Even though Paul was a Roman citizen he was beheaded by Emperor Nero.

That the assassins assumed the Sanhedrin’s leadership would take part in the murder plot says much about the apparent corruption of Isra’el’s highest court. Nor did the Sanhedrin disappoint them (23:20).

That the assassins assumed the Sanhedrin’s leadership would take part in the murder plot says much about the apparent corruption of Isra’el’s highest court. Nor did the Sanhedrin disappoint them (23:20).